Home » Public Transport (Page 23)

Category Archives: Public Transport

Sabit

A common sight along Philippine roads are overloaded public utility vehicles. It may be indicative of how difficult it is to get a ride because such is usually the case when there is a lack of public transport vehicles during peak periods (i.e., when transport demand is greater than the supply of vehicles). That lack maybe due to simply not enough vehicles to address the demand or that there is enough on paper and operating but they are not able to make the return trips fast enough. The first case means demand has grown but the number and capacity of vehicles have not kept pace with the demand. The second means that technically there are enough vehicles (franchises) but the traffic conditions along the route have worsened and has resulted in vehicles not being able to travel fast enough to cover the demand.

Jeepney with 6 passengers hanging by the back. All look like they are laborers or workers (construction?) but it is not uncommon to see students in their school uniform similarly dangling from jeepneys especially during the peak hours when its difficulty to get a ride.

Jeepney with 6 passengers hanging by the back. All look like they are laborers or workers (construction?) but it is not uncommon to see students in their school uniform similarly dangling from jeepneys especially during the peak hours when its difficulty to get a ride.

Sabit is actually illegal and, if enforcers are strict, will incur apprehension and a ticket. Many local enforcers including those of the MMDA though are lax about this especially during peak periods. Jeepney drivers are more cautious when they know that Land Transportation Office (LTO) enforcement units are on watch as these are usually strict about passengers dangling from the vehicles. Newer jeepney/jitney models basically eliminated sabit as the doors are now on the right side of the jeepney instead of the back and there are no spaces or features to hold and step on to in the new models. It is for good as this is an unsafe situation for the passengers and there are reckless jeepney drivers who tend to exacerbate the situation by deliberately maneuvering the jeepney as if he wants passengers to fall off the vehicle. To those looking for a thrill (or death wish as a friend calls it), it is an exhilarating experience. But in most cases, it is a disaster waiting to happen.

–

Modified jeepneys?

I spotted this modified jeepney along my commute between Antipolo and Quezon City. The jeepney has been modified so its door is no longer at the back like most jeepneys but at the right side. Judging from the design and the license plate, this was not a “new” jeepney though its the first time I saw this along my regular commute.

Modified jeepney plying the Antipolo-Cubao (via Sumulong Highway) route

Modified jeepney plying the Antipolo-Cubao (via Sumulong Highway) route

The design is a safer one as passengers board and alight from the right side and to the sidewalk (assuming the jeepney driver positions the vehicle in the right manner for a stop). A back door meant passengers boarded and alighted in front of another vehicle or is exposed to traffic. This reminded me also about the designs for LPG jeepney models that were rolled out more than a decade ago but didn’t really take off. The electric jeepneys also have models with the side door that is now found in most models including non-electrics in the modernization program. Perhaps the government should require all jeepneys to be at least retrofitted this way?

–

Cooperative work among LGUs to address transport problems along Ortigas Avenue Extension?

I saw a recent post about a meeting hosted by Pasig City. The Mayor of Pasig City recently held a meeting where he invited the mayors or Antipolo, Cainta and Taytay to discuss, among other things perhaps, transportation along Ortigas Avenue. Ortigas Avenue is a corridor shared by several LGUs most notably the Rizal towns of Antipolo (which is the provincial capital and a highly urbanized city), Cainta and Taytay. The latter two are among the richest municipalities in the country; a fact I underline here since that also should translate to them having the resources or means to help come up with transport and traffic solutions.

Morning rush traffic starts very early these days. This photo was taken around 6AM on a Thursday along the westbound direction just after the Manggahan Bridge. The pedestrian overpass at C. Raymundo junction is shown and the dark colored buildings are at Robinsons’ Bridgetown development. Note the commuters along the right waiting for a ride.

Morning rush traffic starts very early these days. This photo was taken around 6AM on a Thursday along the westbound direction just after the Manggahan Bridge. The pedestrian overpass at C. Raymundo junction is shown and the dark colored buildings are at Robinsons’ Bridgetown development. Note the commuters along the right waiting for a ride.

Photos paint a thousand words. The Taytay Mayor attended the meeting. He has been under fire for the horrendous traffic caused by the mismanagement of Tikling Junction as well as the Barkadahan Bridge area that was and is supposed to be a major alternative route for Rizalenos heading to their workplaces in Makati and BGC. More recently, there were posts about the traffic signals installed at Tikling Junction that basically invalidates the roundabout concept for the junction. The result last Thursday, the first day of operations for the signals, was hellish traffic that backed up a couple of kilometers along the Manila East Road and Ortigas Ave. Extension (some reports say until Cainta Junction). This, even as the signal settings were supposedly done with help from the MMDA.

Antipolo was represented by its former Mayor and husband to the current one. He also happens to be a former Governor of the Rizal Province and likely to run again as his mother, the current governor, is on her 3rd term. It seems to me that the province is not so interested in solutions for Ortigas Avenue despite most of its constituents traveling through the corridor to get to their workplaces and schools. Marcos Highway is not the main corridor for Rizal towns as it basically carries only Antipolo and maybe some of Tanay (via Sampaloc) traffic. Ortigas Avenue Extension branches into two major roads from Tikling – Ortigas Ave Extension, which ends at the capitol, and the Manila East Road, which connects to practically all of Rizal towns with San Mateo and Rodriguez (Montalban) being the exceptions. It is time for the province to pay attention to this commuting problem experienced daily by her constituents.

The Mayor of Cainta seems not as interested as the others, sending a representative who appears to be not one of the top officials (the traffic chief with a rank of SPO1=Master Sergeant is lower ranked than a councilor) of the Municipality to such an important meeting. In fact, he is currently now embroiled in a controversial faux pas involving himself by not wearing a helmet while riding a motorcycle. What’s more is his downplaying this and appearing to be even justifying the act. He eventually apologized but not before stating his moves. He is not new to publicity (stunts?) and knows how bad publicity still translates to good publicity especially in this days of fake news and trolls (he apparently has many on social media). He seems to forget that transport and traffic solutions for Ortigas Ave will likely benefit anyone seeking reelection or higher office in Rizal. He is on his last term as mayor and the break-up with some of his allies including his former Vice Mayor who ran against him in the last elections shows the limits of his political career. What was rumored as plans to run for Rizal governor might just be downgraded to perhaps Vice Mayor? In any case, he should show more interest and effort in finding solutions beyond traffic management and not by himself but in cooperation with others with whom his jurisdiction shares the problems with. Perhaps the initiative of the Pasig Mayor presents an opportunity for such cooperative work? Many people are very interested in this and will be watching – and hoping.

–

On the issuance of provisional units for ‘modernised’ jeepneys

There seems to be a proliferation of various models of the so-called “modernized jeepneys”. They have been deployed along what the DOTr and LTFRB have tagged as “missionary routes”. The latter term though is confusing because this used to refer to areas that are not yet being served by public transportation, hence the “missionary” aspect of the route. The routes stated on the jeepneys are certainly new but they overlap with existing ones. Thus, the new vehicles are actually additional to the traffic already running along the roads used by the existing (old?) routes. The number of units are said to be “provisional” meaning these are trial numbers of these new vehicles and implying the route and service to be somewhat “experimental”. There can be two reasons here that are actually strongly related to each other: 1) the actual demand for the route is not known, and 2) the corresponding number of vehicles to serve the demand is also unknown. Unknown here likely means there has been little or no effort to determine the demand and number of vehicles to serve that demand. The DOTr and LTFRB arguably is unable to do these estimations or determinations because it simply does not have the capacity and capability to do so; relying on consultants to figure this out. That work though should be in a larger context of rationalizing public transport services. “Provisional” here may just mean “arbitrary” because of the number (say 20 or 30 units?) of units they approve for these new routes.

A ‘modernised’ jeepney with a capacity of 23 passengers. The vehicle is definitely larger than the conventional jeepneys and yet can only carry 23 seated passengers. That’s basically the number of seats for most “patok” jeepneys that are “sampuan” or 10 passengers on each bench plus 2 passengers and the driver in the front seats.

A ‘modernised’ jeepney with a capacity of 23 passengers. The vehicle is definitely larger than the conventional jeepneys and yet can only carry 23 seated passengers. That’s basically the number of seats for most “patok” jeepneys that are “sampuan” or 10 passengers on each bench plus 2 passengers and the driver in the front seats.

Modernized jeepney unloading passengers along the roadside

Modernized jeepney unloading passengers along the roadside

Rationalization should require not only the replacement of old jeepney units that seems to be the objective of the government’s modernization program. Rationalization also entails the determination and deployment of vehicles of suitable passenger capacities for the routes they are to serve. I have stated before that certain routes already require buses instead of jeepneys and that jeepneys should be serving feeder routes instead. Meanwhile, routes (even areas) currently having tricycles as the primary mode of transport would have to be served by jeepneys. Tricycles, after all, are more like taxis than regular public transportation. Such will also mean a reduction in the volumes of these vehicles and, if implemented and monitored strictly, may lead to an improvement in the quality of service of road public transport.

[Note: May I add that although I also use ‘jeepney’ in my articles, these vehicles should be called by their true names – ‘jitneys’. The term jeepney is actually a combination of the words Jeep (US military origins) and jitney (a public utility vehicle usually informal or paratransit offering low fares).]

Is there really a transport or traffic crisis in Metro Manila?

I was interviewed recently for a research project by students enrolled in a journalism class. I was asked by one in the group if we indeed have a transport crisis in Metro Manila. The other quickly added “hindi transport, traffic” (not transport but traffic). And so I replied that both terms are valid but refer to different aspects of the daily travel we call “commuting”. “Traffic” generally refers to the flow of vehicles (and people if we are to be inclusive) while “transport” refers to the modes of travel available to us.

“Commuting” is actually not limited to those taking public transportation. The term refers to all regular travel between two locations. The most common pairs are home – office and home – school. The person traveling may use one or a combination of transport modes for the commute. Walking counts including when it is the only mode used. So if your residence is a building just across from your office then your commute probably would be that short walk crossing the street. In the Philippines, however, like “coke” and “Xerox”, which are brands by the way, we have come to associate “commute” with those taking public transportation.

And so we go back to the question or questions- Do we have a transport and traffic crises? My response was we do have a crisis on both aspects of travel. All indicators state so and it is a wonder many including top government transport officials deny this. Consider the following realities for most commuters at present:

- Longer travel times – what used to be 30-60 minutes one-way commutes have become 60 – 120 (even 180) minute one-way commutes. Many if not most people now have double, even triple, their previous travel times.

- It is more difficult to get a public transport ride – people wait longer to get their rides whether they are in lines at terminals or along the roadside. The latter is worse as you need to compete with others like you wanting to get a ride ahead of others.

- People have to wake up and get out of their homes earlier – it used to be that you can wake up at 6:00AM and be able to get a ride or drive to the workplace or school at 7:00/7:30 AM and get there by 8:00 or 9:00AM. Nowadays, you see a lot of people on the road at 5:30AM (even 4:30AM based on what I’ve seen). That means they are waking up earlier than 6:00 AM and its probably worse for school children who either will be fetched by a service vehicle (e.g., school van or bus) or taken by their parents to their schools before going to the workplaces themselves.

- People get home later at night – just when you think the mornings are bad, afternoons, evening and nighttimes might even be worse. Again, it’s hard to get a ride and when you drive, traffic congestion might be at its worst especially since most people leave at about the same time after 5:00PM. Coding people and others not wanting to spend time on the road (instead working overtime – with or without additional pay) leave for their homes later and arrive even later.

- Less trips for public transport vehicles – traffic congestion leads to this. What used to be 6 roundtrips may now be 4. That affect the bottomline of income for road public transport providers. Given the increased demand and reduced rolling stocks of existing rail lines that includes rail transport.

To be continued…

—

Some commentaries on the jeepney modernisation

The nationwide transport strike last Monday elicited a lot of reactions from both supporters and opponents of the the initiatives to modernise the jeepney. Both sides have valid points but both, too, have weak points. Much has been discussed about the cost of acquiring new jeepneys to replace the old ones and whether you agree or not, these are really a bit steep to the typical jeepney driver-operator.

A low downpayment will certainly mean higher monthly amortisations. And most drivers/operators can only afford a low downpayment with or without the 80,000 pesos or so subsidy from the government. Even if you factor in some tax incentives, the net amount to be paid every month will still be too much for a typical driver/operator. Anyone who’s ever purchased a vehicle, new or used, through a loan should know this, and to deny it means you probably are privileged enough not to take out a loan.

Certainly there are exceptions like certain Beep operations that are supposed to be run like a company or cooperative, and where fleet management techniques allow these to operate more efficiently and cost-effectively. The latter supposedly allows the owners to recover their capital (return of investment) for the purchase of the new jitney units. The reality, however, is that not all routes are good enough for the required revenues and the better earning ones subsidize (forced?) those that are not profitable. The ‘company’ or ‘coop’ can therefore hide these unprofitable cases as the collective performance of the routes they operate along become the basis for assessment.

Snapshot inside a jeepney while waiting for it to fill with passengers

Snapshot inside a jeepney while waiting for it to fill with passengers

It is true that the business model (or what is passed off for one) for jeepney operations is flawed. More so if you place this in the context of transport demand for a metropolis like Metro Manila. That is why perhaps corporatization or cooperatives can probably help in terms of improving processes and practices (e.g., maintenance regimes, deployment). So perhaps this is where government should step in and be more aggressive in organising jeepney drivers and operators. I would even dare say that government should be willing to extend more financial support if significant change in public transport is to be achieved. The Office of the President, Senators and Congressmen enjoy a lot of pork and the numbers for a single year indicate that they can, if willing, purchase new jitneys for their constituencies perhaps focusing on the cities and retiring the old, dilapidated public utility vehicles. That, I think, is a more ‘intelligent’ use to these funds that are allegedly being misused by our politicians.

So, was the strike a success? I think the answer is yes it was. Government cannot deny this as it was forced to suspend classes in schools in order to address the impending shortfall of services during the strike and many LGUs were forced to provide free transport services (libreng sakay) in many forms (e.g., dump trucks, flat bed trucks, etc.). You can only say it was a failure if it was business as usual with commuters feeling minimal impact of the stoppage in jeepney operations.

–

Mixed messages for commuters?

I had spotted buses (or perhaps its just the same bus?) for a P2P service between Antipolo and Ortigas Center bearing what appears to be a statement for improving the quality of life of commuters. Many have been suffering and continue to suffer on their daily commutes starting from difficulties getting a ride to very long travel times. The term “dignity of travel” comes to mind, which a colleague coined many years ago to describe

P2P buses at the public transport terminal at Robinsons Place Antipolo

P2P buses at the public transport terminal at Robinsons Place Antipolo

Whoever thought of this probably meant well; thinking about improving quality of life. The choice of words though may convey a different message as “driving” is in all caps and usually associated with a different, less appealing activity to sustainable transport advocates. I think they should have chosen “improving” instead of “driving” here.

Whoever thought of this probably meant well; thinking about improving quality of life. The choice of words though may convey a different message as “driving” is in all caps and usually associated with a different, less appealing activity to sustainable transport advocates. I think they should have chosen “improving” instead of “driving” here.

This is somewhat similar to a much earlier post of mine showing SMRT buses in Singapore with ads promoting Uber and how it was supposed to complement public transport. That, of course, was a bit of a stretch in the city-state, which already has excellent public transport compared to elsewhere, and already complemented by very good taxi services.

Yesterday, there was a nationwide transport strike and depending on which side you are on, the reality is that we are still far from having more efficient public transport. But that’s another story and hopefully, I get to write about it in the next few days.

–

On commuting characteristics in Metro Manila – Part 2

Late last month, I wrote some comments about a recent survey conducted by a group advocating for improved public transport services in Metro Manila. In that post I stated that perhaps its not a lack of public transport vehicles but that they are not traveling fast enough to go around. Simply, the turnaround times for these vehicles are too long and that’s mainly due to congestion. But how do we translate the discussion into something of quantities that will allow us to understand what is really happening to road-based public transport.

As an example, and so that we have some numbers to refer to, allow me to use data from a study we conducted in 2008. Following are a summary of data we collected on jeepneys operating in Metro Manila and its surrounding areas.

| Route Class | Coverage Distance | Distance traveled per day, km |

| Short | 5 kilometers or less | 68.75 |

| Medium | 6 – 9 kilometers | 98.24 |

| Long | 10 – 19 kilometers | 111.22 |

| Extra Long | 20 kilometers & above | 164.00 |

[Source: Regidor, Vergel & Napalang, 2009, Environment Friendly Paratransit: Re-Engineering the Jeepney, Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol. 7.]

Coverage distance refers to the one-way distance between origins and destinations. If we used the averages for the coverage distances for each route class, we can obtain an estimate of the number of round trips made by jeepneys for each route class. We assume the following average round-trip distances for each: short = 3.5 x 2 = 7km; medium = 7.5 x 2 = 15km; long = 14.5 x 2 = 29km; and extra long = 50 km. The last is not at all unreasonable considering, for example, that the Antipolo-Cuba (via Sumulong) route is about 22km, one way, and there are certainly other routes longer than this.

The number of round trips can then be estimated as: short = 68.75/7 = 9.82 or 10 roundtrips/day; medium = 98.24/15 = 6.54 or 6.5 roundtrips/day; long = 111.22/29 = 3.84 or 4 roundtrips/day; and extra long = 164/50 = 3.28 or 3 roundtrips/day. Do these numbers make sense? These are just estimates from 2008/2009. Perhaps everyone would be familiar with certain routes for their regular commutes and the number of roundtrips made by jeepneys (or buses or UV express) there then and now. Short routes like those of the UP Ikot jeepneys might have more roundtrips per day compared to other “short” route jeepneys since there is practically no congestion all day along the Ikot route. It would be worse in the case of others especially those running along the busiest corridors like Ortigas Ave., Marcos Highway, Commonwealth, Espana Avenue, Shaw Boulevard and others. If you factor current travel speeds into the equation then it can be pretty clear how these vehicles are not able to come back to address the demand for them.

In a recent Senate hearing tackling the transport issues in Metro Manila, a certain study was mentioned. This was the EDSA Bus Revalidation Study conducted in 2005/2006. The findings of that study and subsequent ones showed that there was an oversupply of public transport vehicles in Metro Manila. These studies also recommended for the rationalisation or optimisation of road public transport routes in the megalopolis. I think it is timely to revisit these reports rather than pretend there never were formal studies on public transport in Metro Manila and its surrounding areas.

–

On commuting characteristics in Metro Manila – Part 1

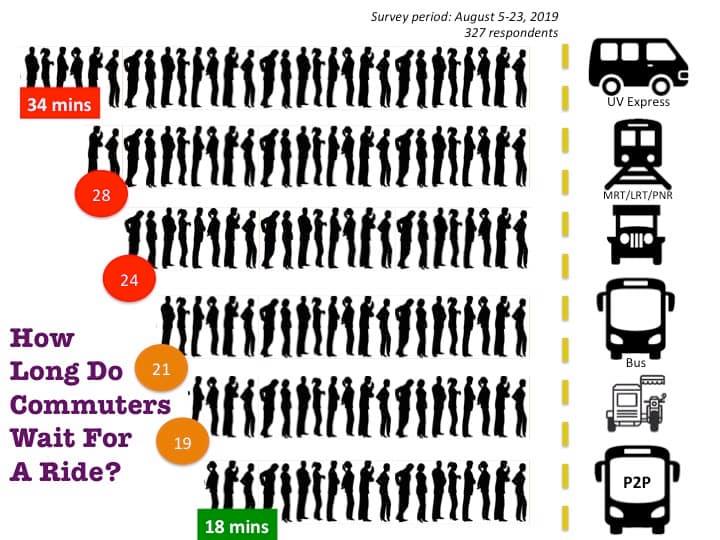

A friend posted the following two graphics showing commuting characteristics derived from a recent survey they conducted online. The 327 respondents are not much compared to the more comprehensive surveys like the ones undertaken by JICA and there are surely questions about the randomness of the survey. Online surveys like the one they ran can be biased depending on the respondents. This was mainly done via social media and through certain interest groups so statistically there may be flaws here. Still, there is value here considering there is often a lack of hard data on commuting characteristics especially those that are recent or current. We need these to properly assess the state of transportation or travel in Metro Manila and elsewhere.

What’s lacking? Information on car and motorcycle users? And why the long waiting times? Are these really just because of a shortage in the supply of public transport vehicles thereby necessitating additional franchises? [Graphic and data courtesy of Toix Cerna via Facebook]

What’s lacking? Information on car and motorcycle users? And why the long waiting times? Are these really just because of a shortage in the supply of public transport vehicles thereby necessitating additional franchises? [Graphic and data courtesy of Toix Cerna via Facebook]

Again, the mode shares reported are incomplete. With the exception of walking, car and motorcycle shares are substantial and significant. There is some info here about trip chains (i.e., the average of 2 rides per commute) but it is unclear what percentage of the trip is made using whatever mode is used. [Graphic and data courtesy of Toix Cerna via Facebook]

Again, the mode shares reported are incomplete. With the exception of walking, car and motorcycle shares are substantial and significant. There is some info here about trip chains (i.e., the average of 2 rides per commute) but it is unclear what percentage of the trip is made using whatever mode is used. [Graphic and data courtesy of Toix Cerna via Facebook]

The absence of information about cars and motorcycles is glaring due to their significant share of commuters. Yes, the term ‘commuter’ actually refers to someone who regularly travels between home and office. By extension, this may also apply to travels between home and school. The term is not exclusive to public transport users as is often assumed. Walking between home and office qualifies as a commute.

I am curious about how commutes using cars and motorcycles would compare to public transport commutes. The comparison is quite useful to show, for example, the advantages and disadvantages of car use (this includes taxis and ride share). More detailed information may also reveal who among car or motorcycle users use these vehicles out of necessity rather than as one among many choices for their commutes. One thinking is that if public transport quality is improved, then many people will opt to use PT rather than their private vehicles. However, there is also the observation that in many cases, those already using PT are the first to shift from the lower quality service to the better one. I also wrote about this as I posted my worries about how successful can Line 7 and Line 2 extension be in reducing car use along their corridors. Perhaps the ones who will truly benefit are those who are already taking public transport, and car and motorcycle users will just continue with these modes?

In Part 2, I will share some data we collected more than a decade ago for a study on jeepneys in Metro Manila. I will use the information to explain another angle of this issue on public transport supply and demand.

–

Quick share: “The ‘War on Cars’ is a Bad Joke

Here is another quick share. This time it is an article that I think attempts to diffuse what some many people regard as a war on cars being waged by those who advocate for public and active transport.

Litman, T. (2019) The ‘War on Cars’ is a Bad Joke, Planetizen, https://www.planetizen.com/blogs/105877-war-cars-bad-joke?fbclid=IwAR2_SZHQeYEUGiU2G8RUw0Za6GrkR-2peD3eSjshpNUOg9-G5SpDWm6OnFI [Last accessed: 8/25/2019]

The author makes very strong arguments supported by evidence and data to place this topic in the right context. That is, there is no need to “wage war” or use arguments that are more on the hateful side and therefore not constructive to both sides. I think there should be a mutual understanding of the benefits (and costs) of having many options for transport or commuting. That said, infrastructure or facilities should not heavily favour one mode (car-centric?) for transport to be sustainable and healthy.

Sadly, many so-called progressives (yes, I am referring to the younger generations who are still in the idealistic stage of their lives) appear to be blind to understanding but instead opt for the hardline stance vs. cars and those who use them. Instead of winning people over and convincing those who really don’t need to drive to take other modes, they end up with more people becoming more apathetic or unwilling to take a stand vs. the status quo. This is the very same status quo that is definitely degrading quality of life and is described as an assault to human dignity.

–