Home » Land use (Page 9)

Category Archives: Land use

Local papers presented at the EASTS 2015 conference – De La Salle University

De La Salle University (DLSU) has a strong program in transportation engineering and planning. This program is under its Department of Civil Engineering and led by Dr Alexis Fillone. Following is a list of papers from DLSU:

- Mode Shift Behavior of Bus Passengers to Rail System under Improved Rail Conditions [Alexis Fillone & Germaine Ann Dilay]

- Evaluating Proposed Transportation infrastructure Projects in Metro Manila using the Transport Co-Benefit Analysis [Alexis Fillone]

- Inter-Island Travel Mode Choice Analysis: Western Visayas Region, Philippines [Nicanor Roxas Jr & Alexis Fillone]

- Revisiting Volume-Delay-Functions Used in Transport Studies in Metro Manila [Jiaan Regis Gesalem & Alexis Fillone]

- Characterizing Bus Passenger Demand along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA), Metro Manila [Sean Johnlee Ting, Kervin Joshua Lucas & Alexis Fillone]

- Optimized Bus Schedules in Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA), Metro Manila Using Fuzzy Rule-Based System [Alexis Fillone, Elmer Dadios & Ramon Intal]

- Opinion Survey about Pedestrianization of Heritage Sites in the City of Iloilo, Philippines [Alexis Fillone & Frederick Sosuan]

- Factors Influencing Footbridge Usage Along Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA), Metro Manila [Aaron King, Rigel Cadag, Jireh Despabiladeras, Rei Tumambing & Alexis Fillone]

- A Compact Scheduling and Revenue Estimation Spreadsheet for Bus Operators [Raymund Abad & Alexis Fillone]

- Adaptive Driving Route of Busses along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA), Metro Manila, using Fuzzy Logic [Alexis Fillone, Bernard Yasay & Elmer Dadios]

I thought DLSU could have published more papers in this conference. I was actually surprised that all the papers are practically attributed to Dr Fillone considering his co-authors are mostly his students. But then there are only 2 to 3 faculty members who are doing transport research in DLSU and Dr Fillone is the most involved and prolific among them in terms of published research outputs.

–

EASTS 2015 – Cebu City, September 11-13, 2015

The 11th International Conference of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies (EASTS 2015) will be held in Cebu City this September 11-13, 2015. For information on the conference and program, check out their website here:

You can also download a brochure about EASTS here:

The conference is hosted by the Transportation Science Society of the Philippines (TSSP), which is the local affiliate of the EASTS. More information on the TSSP are found below:

–

Running out of answers? How about congestion pricing?

A lot of people ask me about solutions to transport and traffic problems. Some are very general like the question “How do we solve traffic congestion in Metro Manila?” and others are more specific like “How do we solve congestion along EDSA?” These questions are becoming quite tricky because, for one, we are running out of answers of the ‘short term’ kind. All these ‘stop-gap’ or ‘band aid’ measures will only provide short-term relief and we have used many of them already including vehicle restraint measures we are very familiar with like the number coding and truck ban schemes currently implemented in the metropolis.

The general answer and likely an inconvenient truth is that we can’t solve congestion. It is here to stay and is a given considering the continued growth experienced throughout the country. Accepting this phenomenon of congestion, we can proceed towards managing it and work towards alleviating it. Denying that there is a problem or dismissing such as an issue requiring urgent action sets a dangerous course towards unsuitable responses or worse, inaction on the part of the government.

Like cholesterol, there is good congestion and bad congestion. Good traffic congestion is when it is predictable in occurrence and period. For example, the morning rush hour is termed so because it used to last only about an hour or so. Congestion occurring between 7:30 – 8:30 AM is okay but between 6:30 – 11:30 AM is undesirable. The cases between those two vary in acceptability based on the tolerance levels of commuters. In Metro Manila, for example, many people probably have been conditioned to think that 2-hour congestion is okay but more than that is severe. This is actually related to travel times or the time it takes to travel between, say, one’s home and workplace.

And so, are there better options other than a return to the “Odd-Even” scheme? There are actually many other options but they are more complicated to the point that many are unpalatable to people who are in a hurry to get a solution our traffic mess. Note that this is to get out of a hole that’s deep enough already but they still managed to dig deeper the last 5 years. Among these solutions would be congestion pricing.

Singapore offers a successful model for this where tolls vary according to the levels of congestion for these roads. There is a base rate for peak periods when congestion is most likely or expected. The government determines the desirable speed ranges along roads as a basis for congestion charges. Along urban streets, that range may be between 20 – 30 km/h. If speeds reduce to below 20 km/h (i.e., congested) then charges or tolls increase. If speeds increased to above 30 km/h, the rates decrease. The image below is screen capture from a presentation made by an official of Singapore’s Land Transportation Authority (LTA).

Note the item on the scheme being ‘equitable’ that is very essential in understanding how road space must be shared among users and that there is an option to use public transport instead. This scheme, of course, will require a lot of consultations but the technical part should not be worrisome given the wealth of talent at universities, private sector and government agencies who can be involved in the analysis and simulations. Important here also is to determine or institute where the money collected from congestion pricing will go. Logic tells us that this should go to public transportation infrastructure and services. In Singapore, a big part of the funds collected from ERP goes to mass transit including their SMRT trains and buses. Funds help build, operate and maintain their trains and buses. The city-state already has a good public transport system that is subsidized by congestion charges and this system is able to attract people from using their cars especially during the weekdays when transport is used for work and school trips. That way, people who don’t really need to own and use their cars are discouraged from doing so (Note: This works together with Singapore’s restrictive car ownership policies.).

Would it be possible to have congestion pricing for Metro Manila or other cities in the Philippines? Yes, it is and but entails a lot of serious effort for it to work the right way. We can probably start by identifying major roads whose volumes we want regulated, installing sensors for monitoring traffic conditions and tagging vehicles and requiring most if not all vehicles to have transponders for motorists to be charges accordingly. However, there should be an attractive and efficient public transport option for this program to work. Unfortunately, we don’t have such along most roads. Perhaps an experiment or simulation can be undertaken once the LRT 2 extension is completed and operational? That corridor of Marcos Highway and Aurora Boulevard, I believe is a good candidate for congestion pricing.

With the sophisticated software that are now available, it is possible to conduct studies that would employ modelling and simulation to determine the potential impacts of congestion pricing on traffic. It should have a significant impact on congestion reduction even without mass transit systems such as Singapore’s. However, without good public transport, it would be punishing for people who are currently using their own vehicles to avoid taking public transport. I used the term ‘punishing’ because congestion pricing will be a back breaker for people who purchased vehicles to improve their commutes (i.e., they likely were not satisfied with taking public transportation). These are the working people and part of the small middle class whose transport needs should be addressed with urgency.

–

Transport wish list for 2015

Last year, I opened with a very hopeful post on opportunities with certain mass transit projects that were hyped to be starting construction in 2014. The year 2014 went by and practically nothing really concrete happened (Yes, there were soil tests conducted for the LRT 2 extension but after that nothing else happened with the project.) with respect to these very critical mass transit projects that were already much delayed. It’s the same thing again this year so that same blog post from Jan. 1, 2014 applies this year.

I will not write down a list of New Year’s resolutions for the transport-related government agencies to adopt this 2015 though that stuff is quite tempting to do. Instead, I will just rattle of a wish list that includes very general and very specific programs and projects I would like to see realized or implemented (e.g., start construction) within the year; preferably from the first quarter and not the last. For brevity, I came up only with a list of 10 items. It is not necessarily a Top Ten list as it was difficult for me to rank these projects.

1. LRT Line 2 Extension from Santolan to Masinag

2. LRT Line 1 Extension to Cavite

3. MRT Line 7 from Quezon City to San Jose del Monte, Bulacan

4. Cebu BRT

5. People-friendly road designs

6. Integrated fare collection system for Metro Manila trains

7. Bikeways in major cities

8. Any mass transit project for Davao City or any other major city outside of Metro Manila or Cebu

9. Northrail or whatever it is that will connect Metro Manila with Clark

10. Protection of heritage homes and sites along highways and streets

The reader is free to agree or disagree with the list or to add to the list. I’m sure there are a lot of other projects out there that are also quite urgent that are not on my list but are likely to be equally important.

–

Let’s revisit the Marikina Bikeways

Calls for more walkable and bicycle-friendly cities and a lack of local data for these modes of transport got me thinking about Marikina. The city has its own bikeways office, the Marikina City Bikeways Office (MCBO), that was under City Planning and Development Office but borrowed staff from other offices of the city. The MCBO has gone through many challenges since the time of Bayani Fernando, who instituted the office, and his wife Ma. Lourdes under whose terms the office was downgraded. I’ve learned that the office has been strengthened recently and is implementing a few programs to promote cycling especially among school children. I wonder, though, if Marikina has been collecting and keeping tabs on cycling related data. I recall that during the conduct of the study for the Marikina bikeways network, it was established that there was a dearth of data on cycling and data collected pointed to cyclists primarily comprised of workers in factories or construction sites in the city and neighbouring areas. These are the regular commuters using bicycles instead of motorised vehicles. It would be nice to see if these increased in numbers (observations along major roads like Sumulong Highway seems to support the increase) and if there have also been shifts to motorcycles as the latter became more affordable in recent years. Enforcement is still an issue with regards to the bikeways as not all paths are segregated. As such, those lanes painted on the roads are more susceptible to encroachment by motorised vehicles. Still, Marikina is a very good example of realising people-friendly infrastructure and many LGUs could learn from the city’s experiences with the bikeways.

A bicycle bridge along Sumulong Highway in Marikina City

A bicycle bridge along Sumulong Highway in Marikina City

Recently, some students consulted about designing bikeways in other cities as well as in a bike sharing program being planned for the University of the Philippines Diliman campus. These are good indicators of the interest in cycling that includes what discussions on the design of cycling facilities and programs intended to promote bicycle use especially among young people. We strongly recommended for them to check out Marikina to see the variety of treatments for bikeways as well as the examples for ordinances that support and promote cycling.

–

Metro Manila Transport, Land Use and Development Planning Project (MMETROPLAN, 1977)

[Important note: I have noticed that the material on this blog site has been used by certain people to further misinformation including revisionism to credit the Marcos dictatorship and put the blame on subsequent administrations (not that these also had failures of their own). This and other posts on past projects present the facts about the projects and contain minimal opinions, if any on the politics or political economy at the time and afterwards. Do your research and refrain from using the material on this page and others to promote misinformation. I suggest you go to the The Mass Transit System in Metro Manila site for more facts about railway development and history. I do not consent to the use of my articles for the purposes of misinformation and historical revisionism. 10/13/2019]

In a previous article, I had written about the Urban Transport Study for the Manila Metropolitan Area (UTSMMA), which was completed in 1973 and proposed, among others, a rapid rail transit network for Metro Manila. The government proceeded to undertake a feasibility study for the first line of that network almost immediately afterwards. However, something happened a few years later that effectively contradicted UTSMMA’s recommendations and, from what the documents available to us now suggest, effectively doomed the future of transport in Metro Manila.

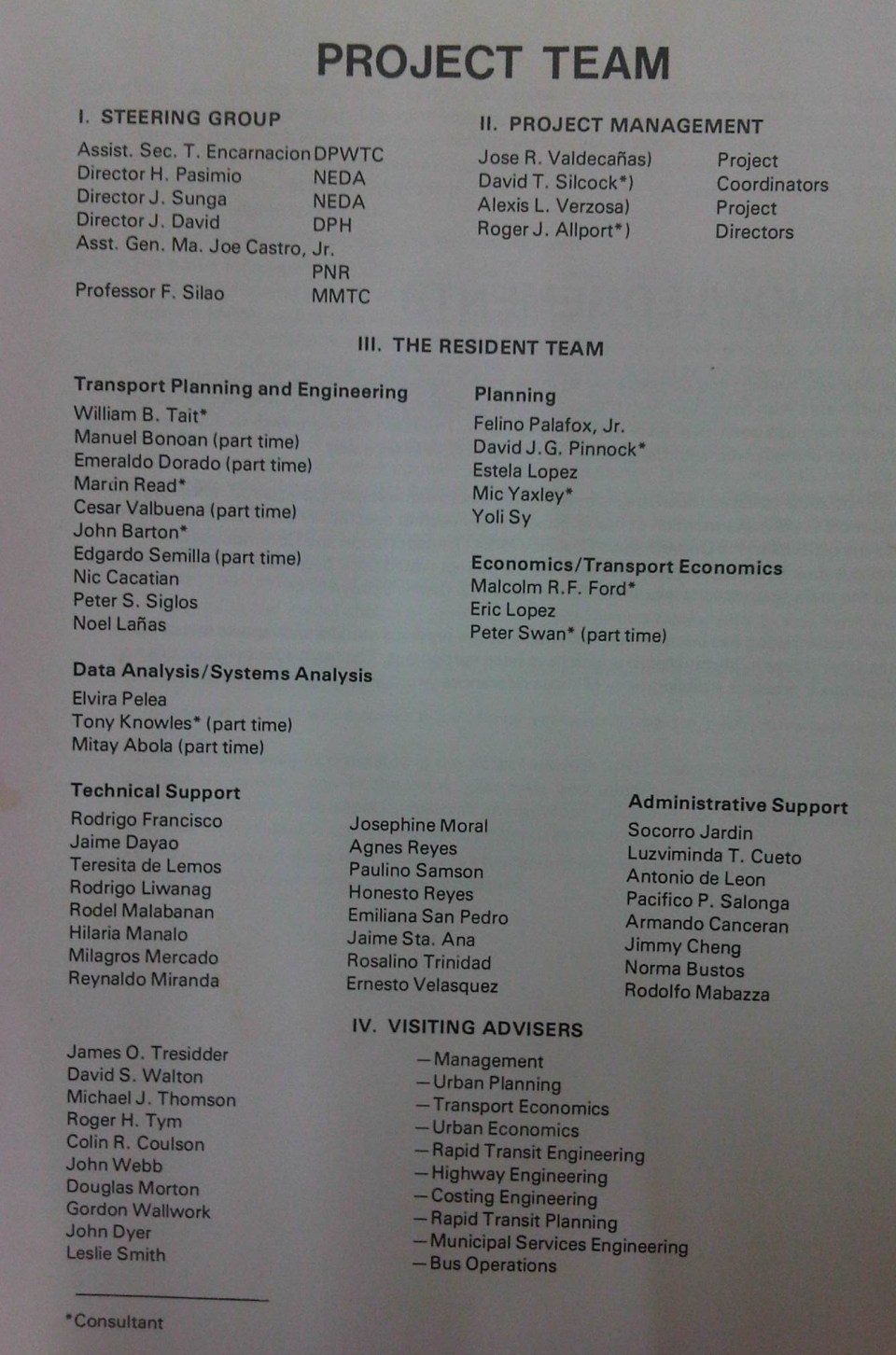

The Metro Manila Transport, Land Use and Development Planning Project (MMETROPLAN) was implemented from January 1976 to February 1977. It was apparently commissioned by the Philippine Government, and funded by the World Bank, which commissioned the precursor of Halcrow Fox to do the study with a steering group comprised of senior government official dealing with transport at the time.

The MMETROPLAN project team is shown in the photo below. Note the inclusion of some familiar names particularly from the DPWH and DOTC who were then with what was the Department of Public Works, Transportation and Communications (DPWTC) and Department of Public Highways (DPH) before these were reorganised. Note, too, a familiar name under Planning, who is very much active today with his own advocacies.

The study is more expansive in terms of scope as it included components on land use and development planning for Metro Manila. It identified three main strategies to address issues on traffic congestion and public transport requirements, namely:

- Cordon pricing,

- Bus lanes, and

- LRT

Short-term recommendations focused on bus and jeepney operations, recommending that:

- Standard buses (non-airconditioned) be designed for more standing passengers and charge a fare affordable by the poor;

- Premium buses (including Love Bus) be designed for seated passengers and charge a higher fare; this may be used to cross-subsidize Standard bus operations;

- Metro Manila Transit Corporation (MMTC) bus operations should not be further expanded:

- MMTC buses should operate missionary routes, which are generally unprofitable routes.

- There should be no arbitrary exemption on franchises like in the case of MMTC.

- In reference to private bus companies, the project states that “properly regulated competition” provides best course of action for the foreseeable future;

- Jeepneys are suited for low demand but high frequency service

MMETROPLAN also touched on the route structure for road public transport. However, its most far-reaching recommendations on road public transport concern the issuance of franchises for buses and jeepneys. The study recommended that franchises should be issued for a period of a few years instead of 25 years and to define a minimum LOS. The study cautioned against arbitrary restrictions on franchises for buses at the time while mentioning that there were already restrictions for jeepneys. MMETROPLAN further recommended the encouraging of small operators for both jeepneys and buses.

However, MMETROPLAN deviated from the recommendations of UTSMMA in that it struck down the proposal and plans for the Rapid Transit Rail (RTR) network for Metro Manila. The long-term recommendations and conclusions of the study show these and one particular recommendation that probably doomed heavy rail transport and the RTR network is quoted below:

“Heavy Rapid Transit (HRT) would provide public transport passengers with much faster journey, but by 1990 would attract only 2.5% of motorists and would have negligible impact on traffic congestion. Partly because of this and partly because of its very high capital cost, it would be hopelessly uneconomic: the annualized capital costs would be higher than the estimated benefits in 1990…passenger flows are not high enough to exploit its full capacity…and the large savings in time for public transport passengers are not given a high value in Manila, and are not high enough to persuade motorists to change mode.

These results are conclusive, and are unlikely to be changed by any circumstances or reasonable assumptions…it is clear that any other fully segregated public transport system, whether light rail or busway, would also be uneconomic. As such systems would require the appropriation of most, if not all, of the available funds for all transport (including highways) in Metro Manila for the foreseeable future, and as there is not other rationale for their implementation, they have been rejected from further consideration.” (MMETROPLAN, 1977)

The study also did not have good words for the PNR as it concluded that its “routes related poorly to the major demands for movement” and that it would be expensive to improve the PNR at the time. PNR costs were compared to buses and jeepneys with the further concluded that these road transport modes are preferred over an upgraded PNR.

MMETROPLAN assessed the LRT vs. the Monorail in the context of cordon pricing and bus lane strategies. While the monorail was dismissed for reasons that included few monorail systems operating at the time, the study recommended for an LRT along Rizal Avenue, which was considered feasible. These conclusions and recommendations by MMETROPLAN would eventually have far-reaching impacts on Metro Manila’s transport system and the study would be among the most cited in discussions and future planning where land use and transport are discussed in the same light.

For land use planning, the report also provides us with a history of land use planning for Metro Manila, which we can now compare with what actually happened. That is, if the plans made back in the 1970’s were actually implemented and to what extent were they realised. Many of these plans remain controversial to this day and are often invoked whenever there is talk about the perennial flooding and the spectre of earthquakes threatening much of Metro Manila and its surrounding areas in addition to other issues like the transport and traffic problems experienced around what has become a megalopolis.

[Reference: MMETROPLAN, 1977 – NCTS Library]

But what could have influenced the MMETROPLAN study team and government officials to debunk UTSMMA? Why the “about-face” for something that seems to be the JICA Dream Plan circa 1970’s? UTSMMA and the rail rapid transit network, after all, was the product of a vision for future Metropolitan Manila transport by a visionary professor from the University of Tokyo – one Dr. Takashi Inouye of that university’s Department of Urban Engineering. I think the next article will provide us with the answers to these questions regarding the turnaround. Abangan!

–

Urban Transport Study in Manila Metropolitan Area (UTSMMA, 1973)

[Important note: I have noticed that the material on this blog site has been used by certain people to further misinformation including revisionism to credit the Marcos dictatorship and put the blame on subsequent administrations (not that these also had failures of their own). This and other posts on past projects present the facts about the projects and contain minimal opinions, if any on the politics or political economy at the time and afterwards. Do your research and refrain from using the material on this page and others to promote misinformation. I suggest you go to the The Mass Transit System in Metro Manila site for more facts about railway development and history. I do not consent to the use of my articles for the purposes of misinformation and historical revisionism. 10/13/2019]

With the recent approval of JICA’s Dream Plan for Mega Manila, I thought it was timely to look back at similar plans developed for Metro Manila and its surrounding areas. At the time these plans were made, I guess they were all regarded as “dream plans” in their own ways. Let us start with what is probably the original dream plan, the Urban Transport Study in Manila Metropolitan Area (UTSMMA, 1973). The project was implemented from March 1971 to September 1973 with the assistance of the Government of Japan’s Overseas Technical Cooperation Agency (OTCA), the precursor of today’s Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Being the first comprehensive study for a metropolitan area that was yet to be formally consolidated and called Metro Manila, UTSMMA set the stage for future transport studies for the metropolis. Among the study’s main recommendations is one proposing for a mass transit system restricted to railways. A Rapid Transit Railway (RTR) network was recommended in the form of subways in the inner area bound by EDSA, and elevated in the suburban areas. Brief descriptions of the proposed lines are as follows:

- Line 1 (27.1 km) – from Construction Hill to Talon via central Quezon Boulevard, Manila downtown and the International Airport

- Line 2 (36.0 km) – from Novaliches to Cainta via Manila downtown and Pasig

- Line 3 (24.3 km) – Along Highway 54 (C-4): half a circle route about 12 km from Manila downtown

- Line 4 (30.1 km) – From Marikina to Zapote via Cubao, Manila downtown and the Manila Bay area

- Line 5 (17.6 km) – From Meycauayan to Manila downtown running between Line No. 2 and PNR

- PNR improvement (56.4 km) – From Bocaue to Muntinglupa via Tutuban Station

The following that was posted here before in another article shows a map illustrating the recommended RTR network for the Manila Metropolitan area. (Note that the map was enhanced from the original black and white to clearly show the proposed lines back then.)  UTSMMA also recognized the important roles of buses and jeepneys in the future, and recommended that these be used for feeder services once the rail systems have been constructed and operational. As a result of the study, a Feasibility Study for the Manila Rapid Transit Railway Line No. 1 was conducted and completed in June 1976. The study, which was supported by JICA, noted that “the implementation should be initiated immediately” in light of the estimated heavy traffic demand along the corridor. This project could have been the first major transport project for Metro Manila if it had been implemented. Unfortunately, despite a favorable assessment in this study, the proposed RTR Line 1 was not implemented after a contrary assessment by a subsequent study, MMETROPLAN, which is discussed in the succeeding section of this report. The estimated costs of construction of recommended transport infrastructure were provided in the Final Report of the study including indicative costs and benefits of proposed urban expressways and urban rapid transit railways. [Reference: UTSMMA, 1973 – NCTS Library] Whenever I go back to UTSMMA and the network of proposed railway lines, I can’t help but wonder what could have been one of the more efficient transport systems in Asia or even in the world. What happened? Why was this plan not realised? The answer may be found in the next big study conducted for Metro Manila that also included in much detail its land use and development plans. Next: MMETROPLAN, 1977 –

UTSMMA also recognized the important roles of buses and jeepneys in the future, and recommended that these be used for feeder services once the rail systems have been constructed and operational. As a result of the study, a Feasibility Study for the Manila Rapid Transit Railway Line No. 1 was conducted and completed in June 1976. The study, which was supported by JICA, noted that “the implementation should be initiated immediately” in light of the estimated heavy traffic demand along the corridor. This project could have been the first major transport project for Metro Manila if it had been implemented. Unfortunately, despite a favorable assessment in this study, the proposed RTR Line 1 was not implemented after a contrary assessment by a subsequent study, MMETROPLAN, which is discussed in the succeeding section of this report. The estimated costs of construction of recommended transport infrastructure were provided in the Final Report of the study including indicative costs and benefits of proposed urban expressways and urban rapid transit railways. [Reference: UTSMMA, 1973 – NCTS Library] Whenever I go back to UTSMMA and the network of proposed railway lines, I can’t help but wonder what could have been one of the more efficient transport systems in Asia or even in the world. What happened? Why was this plan not realised? The answer may be found in the next big study conducted for Metro Manila that also included in much detail its land use and development plans. Next: MMETROPLAN, 1977 –

Required reading on sprawl, transit and the poor

A friend recently posted an article on Facebook that I thought should be required reading for urban and transport planners in the Philippines whether they be with government or the private sector. There is a strong link between land use and transport, we need to be able to understand the complexities and subtleties in order to maximize the benefits to society. It is not a coincidence that the article specifically mentions the poor as it discusses opportunities lost due to flaws or inefficiencies in land use and transport. The article is found in the following link:

Suburban sprawl and bad transit can crush opportunity for the poor

I hope that this will be read and understood by officials at DOTC, LTFRB, LRTA and PNR, as well as those of the Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council (HUDCC) and the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB). These agencies are responsible for planning and regulating transport and housing in the country. Of course, it is also important for local government units to be able to understand these challenges especially since they will be in the forefront of addressing issues on sprawl and the provision of suitable transport systems. Here’s a related article that I posted earlier this year on New Year’s Day:

Opportunities with the MRT-7 and LRT-1 Extension

–

The Philippines’ National EST Strategy – Final Report

Friends and some acquaintances have been asking about whether there is a master plan for sustainable transport in Philippines. There is none, but there is a national strategy that should serve as the basis for the development and implementation of a master plan, whether at the national or local level. This strategy was formulated with assistance of the United Nations Council for Regional Development (UNCRD) through the Philippines’ Department of Transportation and Communication (DOTC) and Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), which served as the focal agencies for this endeavour. The formulation was conducted by the National Center for Transportation Studies (NCTS) of the University of the Philippines Diliman. For reference, you can go to the NCTS website for an electronic copy of the National Environmentally Sustainable Transport Strategy Final Report.

Cover page for the National EST Strategy Final Report

Cover page for the National EST Strategy Final Report

–

Green light for the Cebu BRT

The NEDA Board chaired by the Philippines’ President approved last week a number of major infrastructure projects. One project is particularly important as it seeks to introduce an innovative public transport system in the Philippines. The Cebu Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) project was finally given the green light and is projected to be completed and operational by 2017. I remember that the Cebu BRT was conceptualised while we were doing a social marketing project for Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) that was supported by the UNDP. That was back in 2006-2007 and right before we embarked on the formulation of a national EST strategy that was supported by UNCRD. I remember, too, that sometime in 2009, Enrique Penalosa, the former mayor of Bogota, Colombia who has championed the BRT cause visited the Philippines to give some talks in Cebu and Metro Manila about public transport and pursuit of better quality of life through good transport systems. From that time onwards, a lot of work has been put into the studies to support this system including social marketing for stakeholders to understand what such a system will require including its impacts on existing transport modes. It took sometime for this project to be approved but that should no longer be an issue and focus should now be on the detailed design and implementation of the project.

There are many detractors of this BRT project. While I respect the value engineering work that was supposed to have been conducted by NEDA, I would like to speculate that perhaps it was unclear to them how important a functioning, operational BRT in Cebu is as a strategic accomplishment in transport in this country. For most people, the idea of bus transport is what they have seen along EDSA in Metro Manila. The impact on commuting behaviour of a high quality public transport system like a BRT would be very hard to quantify and the criteria and metrics used would be quite tricky considering the strategic and behavioural aspects of the system. Such evaluations can also be tricky depending on who were doing the study in the first place as the outcomes could easily be affected by the biases of those who undertook the evaluation. Thus, it is important that value engineering exercises be done by open-minded, flexible if not disinterested parties to the project of interest.

Many of those who have expressed skepticism about the BRT are likely pining for a rail transit system that was earlier proposed for the city but which has failed to gain the critical support. For one, the LRT that was proposed for Cebu City was simply too expensive and financing would have been difficult for a system that would have been less flexible in operations compared to an at-grade bus system. The numbers supporting the LRT were also in need of much updating as the study on that system was already quite dated and had not considered the major developments in Cebu and its surrounding cities that loosely or informally comprise what people refer to as Metro Cebu. These realities would need a new and more robust study that could surely result in a recommendation for a rail system but upon close comparison with a BRT option should lead to a conclusion that Cebu will be better off with BRT at this point and in the foreseeable future.

The truth is that while rail transport remains as an ultimate goal for high demand corridors in highly urbanised cities, it is an expensive proposition and ones that will take more time to build. We don’t have that time in our hands as our cities are rapidly growing both in terms of economy and population. We cannot sustain this progress if our transport system remains primitive. And strategically, too, a BRT system may just pave the way for a future rail system in Cebu. This model for transport system development can be replicated in other cities as well including Davao, Iloilo, Bacolod, and Cagayan de Oro, to name a few. But we should always not forget that building this system requires holistic development of complementing infrastructure such as pedestrian walkways and bikeways, and the rationalisation of jeepney and multi cab services with respect to the mass transit system. I believe those behind the Cebu BRT project have these covered and it is now a matter of time before the country’s first BRT becomes operational in the “Queen City of the South.”

–