Home » Public Transport » Paratransit (Page 8)

Category Archives: Paratransit

Rizal Avenue – Part 1: Carriedo – Bambang

Rizal Avenue stretches from Manila northward to Caloocan city from Carriedo to Monumento. What used to be one of the more cosmopolitan streets in Manila was transformed (some say blighted) by the construction of the elevated LRT Line in the early 1980’s. Carriedo, for example, used to be a popular shopping street along with Escolta. Those were times when there were none of the huge shopping malls now scattered in Metro Manila and people came to Manila to shop.

The following photos were taken while we traversed Rizal Avenue as part of a recon we were conducting for a project with the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) back in 2011. I’m not sure if there have been any significant changes along Rizal Avenue and I am not aware of any recent programs to improve conditions under the LRT Line 1.

Approaching the LRT Line 1 Carriedo Station from the McArthur Bridge

Approaching the LRT Line 1 Carriedo Station from the McArthur Bridge

Under Carriedo Station, one experiences first-hand what people have been saying about the area being blighted by the LRT 1 structure

Under Carriedo Station, one experiences first-hand what people have been saying about the area being blighted by the LRT 1 structure

Poorly lighted? It was broad daylight outdoors when we conducted the recon but underneath an LRT 1 Station it can get quite dark. Of course, aside from the need to improve illumination, perhaps authorities can also improve the environment including the cleanliness of the area under the station. A common complaint is garbage and there are those saying the area smells of piss (i.e., mapanghi).

Poorly lighted? It was broad daylight outdoors when we conducted the recon but underneath an LRT 1 Station it can get quite dark. Of course, aside from the need to improve illumination, perhaps authorities can also improve the environment including the cleanliness of the area under the station. A common complaint is garbage and there are those saying the area smells of piss (i.e., mapanghi).

Past Carriedo Station, it was brighter and perhaps the area can be developed so that stretches can be pedestrian friendly. Maybe there should also be restrictions on vehicle parking, which tends to make the area look congested. It would be good to have a strategically located multilevel facility in the area where most vehicles can park instead of along the streets as shown in the photo.

Past Carriedo Station, it was brighter and perhaps the area can be developed so that stretches can be pedestrian friendly. Maybe there should also be restrictions on vehicle parking, which tends to make the area look congested. It would be good to have a strategically located multilevel facility in the area where most vehicles can park instead of along the streets as shown in the photo.

5More roadside parking plus the presence of tricycles contribute to traffic congestion in the area. People are everywhere walking and crossing anywhere. The arcades where they are supposed to walk along are mainly occupied by vendors or merchandise of stores/shops occupying the ground floors of the buildings along the street.

5More roadside parking plus the presence of tricycles contribute to traffic congestion in the area. People are everywhere walking and crossing anywhere. The arcades where they are supposed to walk along are mainly occupied by vendors or merchandise of stores/shops occupying the ground floors of the buildings along the street.

Each side of Rizal Avenue is surprisingly wide with 3 lanes per direction. One lane is effectively used for on-street parking while the other two are for general traffic. There are no lane markings at the time we passed by the area so there can be confusion as to lane assignments.

Each side of Rizal Avenue is surprisingly wide with 3 lanes per direction. One lane is effectively used for on-street parking while the other two are for general traffic. There are no lane markings at the time we passed by the area so there can be confusion as to lane assignments.

Approach to the junction with Recto Ave. and the LRT Line 2, which is also elevated and at the 3rd level as shown in the photo.

Approach to the junction with Recto Ave. and the LRT Line 2, which is also elevated and at the 3rd level as shown in the photo.

Rizal Ave.-Recto Ave. intersection – visible downstream in the photo is Doroteo Jose Station

Rizal Ave.-Recto Ave. intersection – visible downstream in the photo is Doroteo Jose Station

Provincial bus terminal between Doroteo Jose and Bambang Stations

Provincial bus terminal between Doroteo Jose and Bambang Stations

The Sta. Cruz district and particularly the Bambang area is well-known for shops selling medical equipment and supplies. Medical, nursing and other students of allied medical professions as well as professionals come to Bambang to purchase equipment and supplies from these shops, which offer items at lower prices.

The Sta. Cruz district and particularly the Bambang area is well-known for shops selling medical equipment and supplies. Medical, nursing and other students of allied medical professions as well as professionals come to Bambang to purchase equipment and supplies from these shops, which offer items at lower prices.

LRT 1 Bambang Station

LRT 1 Bambang Station

Rizal Ave.-Bambang St. intersection beneath the station

Rizal Ave.-Bambang St. intersection beneath the station

Two large government hospitals are located in the area between Bambang Station and Tayuman Station – San Lazaro Hospital and Jose Reyes Memorial Medical Center. Both are run by the Department of Health (DOH), which is located beside Jose Reyes.

Two large government hospitals are located in the area between Bambang Station and Tayuman Station – San Lazaro Hospital and Jose Reyes Memorial Medical Center. Both are run by the Department of Health (DOH), which is located beside Jose Reyes.

–

Informal transport at PNR Bicutan Station

On our way to a meeting at the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) in Bicutan, Taguig City, we crossed the PNR line running parallel to the SLEX. I quickly took a photo of the scene to the right of our vehicle that showed an informal market and terminal. The informal market or talipapa is one you would usually finally elsewhere in many other places in the city and likely caters to mostly informal settlers residing along the PNR ROW. On our return trip from the DOST, we took the same route and again I quickly took a photo of what was on the other side of the road along the same PNR line. On the other side was the PNR Bicutan Station and what appears to be a clear ROW northbound towards Manila. Much has been accomplished in the clearing of the PNR’s ROW over the past years and the efforts included the relocation of many informal settlers in coordination with the local governments along the PNR line.

The PNR Bicutan Station on the north side of Gen. Santos Ave. near the SLEX Bicutan interchange

The PNR Bicutan Station on the north side of Gen. Santos Ave. near the SLEX Bicutan interchange

Non-motorized trolleys on the south side of Gen. Santos Ave. near the SLEX Bicutan Exit

Non-motorized trolleys on the south side of Gen. Santos Ave. near the SLEX Bicutan Exit

The trolleys are informal transport vehicles serve people living along the PNR ROW including many informal settlements within and without the PNR property. Some of the buildings or structures of these informal settlers are visible in the photo downstream of the railroad crossing. There are similar cases in Manila and elsewhere along the PNR ROW including motorized trolley services in the provinces of Quezon and Camarines Sur, where trolleys are also utilized for public transport and are the means for livelihood by some of the same informal settlers.

There are increasing safety concerns for these vehicles, their operators and their passengers. The trolleys are lifted from the tracks an people clear the way once a train approaches. They return after the train has passed. With the PNR currently experiencing a revival of sorts, and if resources continue along with an increase in ridership, train frequencies should also be expected to increase. As such, there should come a time when trolleys would have to be banned along the entire line in order to minimize the chances for crashes involving trains and trolleys that will surely lead to fatal consequences. Perhaps the local governments along the PNR line should already look into this eventuality and initiate programs to address this issue, which can be associated with livelihood and residential concerns.

–

Rationalizing public transport in the Philippines

I got a copy of the recent study “Development of a Mega Manila Public Transportation Planning Support System” conducted by UP Diliman’s National Center for Transportation Studies (NCTS) for the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC). The main outcome of the study was a planning support system that includes an updated database of bus, jeepney and UV Express routes for Metro Manila and its surrounding areas (collectively called Mega Manila), and a calibrated travel demand model for the region that is supposed to be used by the DOTC and the LTFRB in transport planning including the rationalization of public transport in the region. Among the notable recommendations for addressing public transport issues is the following on the classification of routes according to passenger demand, which I quote from the study:

“…routes and modes may be classified and prioritized as follows:

- Routes with Very High Passenger Demand [>160,000 passengers per day] – shall be served by high capacity modes such as rail-based transit or Bus Rapid Transit(BRT) with passing lanes.

- Routes with High Passenger Demand [100,000 to 160,000 passengers per day] – shall be served by high capacity vehicles such as Bus Rapid Transit System (BRT) without passing lanes;

- Routes with Medium Passenger Demand [10,000 to 100,000 passengers per day] – shall be served by PUVs with 60 or less passengers/seats but not less than 22 passengers (excluding driver) such as buses, CLRVs with more than 22 passengers/seats (including driver), or with 90 passengers/seats in the case of double decker or articulated buses;

- Routes with Low Passenger Demand [not exceeding 10,000 passengers per day] – shall be served by PUVs with less than 22 passengers/seats (including driver) such as jeepneys and other paratransit modes.

Under this principle, high capacity modes would have priority in terms of CPC allocation and transit right of way in a particular route over lower capacity modes with the exception of taxis. The latter, after all, operate as private cars rather than PUVs with fixed routes.

Applications to operate bus and/or minibus service in jeepney routes can be considered, but not the other way around. Similarly, bus service applications can be considered in minibus routes but not otherwise.

Based on the analysis of routes, the establishment of public transportation routes and the corresponding modes of services may be based on the following criteria:

• Passenger demand patterns and characteristics

• Road network configuration

• Corresponding road functions (road hierarchy)

• Traffic capacities and

• Reasonable profits for operation of at most 13% ROI.”

[Source: DOTC (2012) Development of a Mega Manila Public Transportation Planning Support System, Final Report.]

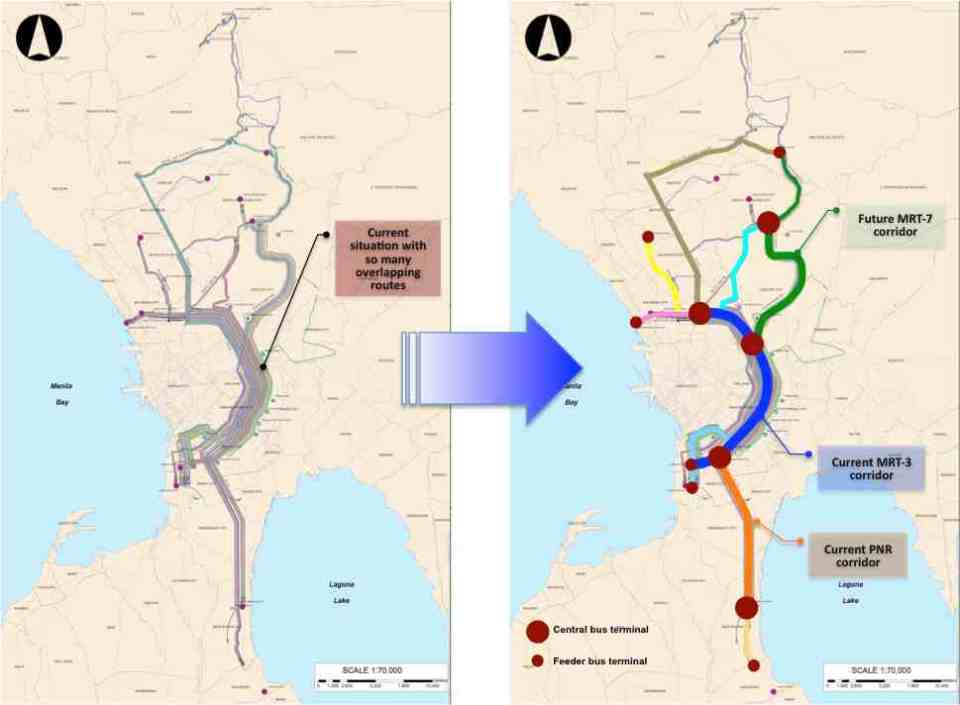

An interesting figure in the report is an illustration of how services can be simplified using buses and rail transport as an example. The following figure shows two maps: one showing the plotted EDSA bus routes (left) and another showing a more consolidated (and rational) route network for buses complementing existing and proposed rail mass transit systems.

Simplifying bus transport services (source: DOTC, 2012)

Simplifying bus transport services (source: DOTC, 2012)

What are not included in the figure above are the prospects for Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems for Metro Manila. Since the Final Report was submitted in mid 2012, there have been many discussions for BRT in the metropolis and current efforts are now focused on the assessment of a BRT line along Ortigas Avenue. The World Bank is supporting the evaluation of a route between Tikling Junction near the boundary of Antipolo and Taytay (Rizal Province) and Aurora Boulevard. There are also informal talks of a BRT line along Commonwealth Avenue but that would have implications on the proposed MRT-7 along the same corridor. Nevertheless, such mass transit systems have long been required for Metro Manila and their construction have been overdue. A more efficient public transport system will definitely have tremendous impacts on how we commute between our homes, workplaces, schools and other destinations. Long distances can easily be addressed by better transport options and could actually help solve issues pertaining to informal settlements, relocations and housing. That topic, of course, deserves an article devoted to this relationship between transport and housing. Abangan!

–

Transport gaps

I first learned about the concept back in the 1990’s when I was a graduate student at UP majoring in transportation engineering. The concept on transport gaps was first mentioned in a lecture by a visiting Japanese professor as he was discussing about transport modes, particularly on which was suitable or preferable over certain travel distances and which could carry more passengers. Another time later and while in Japan, I heard about the concept during a presentation of a friend of his technical paper on public transport.

The figure below is one of many possible illustrations of the concept of transport gaps. In the figure, a distinction is made for mass transport and individual transport. As the original figure is likely taken from a textbook or a paper (probably from Japan), shown with a white background are the more conventional modes of transport including subways, urban and suburban railways, walking and a mention of the shinkansen (more popularly known as the bullet train). With a gray background in the original figure is a category on new urban transit systems that include monorails, AGTs and LRTs. If we attempt to qualify local transport modes such as jeepneys, UV Express, tricycles and pedicabs into the graph, the outcome can be like what is illustrated with different color backgrounds in the figure below.

The concept of transport gaps allow us to visualize which modes are suitable for certain conditions where other established modes of transport may not be available or viable. In the original figure, the gap in Japan is filled by new urban transit systems. In our case, gaps are filled by so-called indigenous transport modes such as jeepneys, multicabs, tricycles, pedicabs and even habal-habal (motorcycle taxis).

There are gaps in the Philippine case probably and partly because of the slow development of public transport systems such as the mass transport modes shown in the preceding figure. There was a significant gap right after World War 2 when the tranvia and other railways were destroyed during the war. That gap was filled by the jeepney. There was also a gap in the early 1990’s that was eventually filled by FX taxis. Such gaps can obviously be filled by more efficient modes of transport but intervention by regulating agencies would be required and rationalizing transport services can only be addressed with the provision of mass transport options complemented by facilities for walking and cycling that will complement these modes.

–

Informal transport in Metro Manila: Quezon City

Passing along East Avenue in Quezon City one morning, I couldn’t help but notice the pedicabs (non-motorized 3-wheelers) lined up near the junction from Agham Road in what is just one of the so many informal transport terminals in this city. The motorized tricycle in the photo below is just a bonus but also notable as they weren’t supposed to be running along national roads like East Avenue. They are well within the sight of the Land Transportation Office (LTO) and the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) – two agencies charged with vehicle regulation though these 3-wheeled public transport modes are technically not under the LTFRB and LTO has no jurisdiction over NMTs. I suppose that the local government is well aware of their existence as their operations are legitimized through local regulations.

Tricycles and pedicabs at the junction of East Avenue and Agham Road

Tricycles and pedicabs at the junction of East Avenue and Agham Road

The proliferation of these modes and particularly the non-motorized 3-wheelers are due to the toleration if not encouragement from the local government. These are examples of “accommodations” and tolerance due to these being a source of livelihood for many informal settlers who typically operate these vehicles. In the case of the scene in the photo above, there is the proliferation (and over-supply) of these 3-wheelers whose drivers and operators make a living out of people not willing to walk because of poor facilities or perhaps out of sheer “katamaran.” In many cases, operators and drivers are residents of informal settlements such as those along Agham Road. God forbid that some of these are unlawful people who take advantage of passengers including unsuspecting or absent-minded students and office workers.

Are these forms of transport suitable for this setting? Are they safe forms of transport? Shouldn’t there be a drive to have better pedestrian facilities and more “formal” transport services for a city’s constituents? These are persistent questions that theoretically have answers in terms of good practices found elsewhere. However, in many Philippine cases solutions are dependent on how progressive and serious LGUs are with dealing with these issues. Success is dependent on the initiatives of the LGUs who are in the front lines when addressing concerns on local public transport.

–

V. Luna Extension

V. Luna Extension starts from the intersection with Kalayaan Avenue runs until the boundary with Bgy. Botocan in Teachers Village where it becomes Maginhawa Street. It was mainly a residential street being practically part of the Teachers Village/Sikatuna Village area in Quezon City. The street has been widened to 4 lanes from its wide 2-lane carriageway. However, the additional lanes are not fully utilized for traffic. Rather, they are occupied by parked vehicles and, at some sections, informal tricycle terminals. Following are photos taken one weekday afternoon showing typical conditions along the road.

Section in front of SaveMore – while there are off-street parking spaces available at the supermarket side of the road and reducing on-street parking there, the other side’s curbside lane is occupied by a tricycle queue.

Section in front of SaveMore – while there are off-street parking spaces available at the supermarket side of the road and reducing on-street parking there, the other side’s curbside lane is occupied by a tricycle queue.

The tricycle queue extends well beyond the head shown in the previous photo. In the picture above, on-street parking in front of residential buildings along the street are shown. There is a yellow line painted on the pavement that seems to be a guide for the tricycles. While I am sure they try their best to park close to the curbside, these 3-wheelers still end up occupying significant road space, thereby reducing traffic capacity.

The tricycle queue extends well beyond the head shown in the previous photo. In the picture above, on-street parking in front of residential buildings along the street are shown. There is a yellow line painted on the pavement that seems to be a guide for the tricycles. While I am sure they try their best to park close to the curbside, these 3-wheelers still end up occupying significant road space, thereby reducing traffic capacity.

Further down the street one starts to realize that the tricycle queue seems to go on and as far as the eye could see in the photo. Note the tricycles parked on the other side of the road, probably just coming back or going around to get fares.

Further down the street one starts to realize that the tricycle queue seems to go on and as far as the eye could see in the photo. Note the tricycles parked on the other side of the road, probably just coming back or going around to get fares.

End of the line – still further down the street and quire near the end of the section designated as V. Luna Extension one can already see the end of the tricycle queue. One can just imagine how many more of these tricycles are going around the village and just how much drivers take home as their net income at the end of a very competitive day. I say competitive here because for the numbers alone at the informal terminal, you get the idea that demand is quite limited and that there is an over-supply of 3-wheelers in the area. Unfortunately, these transport modes are the source of livelihood for many people and to many, a career operating these vehicles seem to be targets for many who have limited opportunities to study and eventually find better-paying jobs.

End of the line – still further down the street and quire near the end of the section designated as V. Luna Extension one can already see the end of the tricycle queue. One can just imagine how many more of these tricycles are going around the village and just how much drivers take home as their net income at the end of a very competitive day. I say competitive here because for the numbers alone at the informal terminal, you get the idea that demand is quite limited and that there is an over-supply of 3-wheelers in the area. Unfortunately, these transport modes are the source of livelihood for many people and to many, a career operating these vehicles seem to be targets for many who have limited opportunities to study and eventually find better-paying jobs.

Pedestrian crossings – from the previous photos, it is not hard to see that there are few places designated for crossings. In fact, along the entire length of this street (and others like it) people cross just about anywhere. This is possible since traffic is still typically not so heavy along this street.

Pedestrian crossings – from the previous photos, it is not hard to see that there are few places designated for crossings. In fact, along the entire length of this street (and others like it) people cross just about anywhere. This is possible since traffic is still typically not so heavy along this street.

Fork in the road – V. Luna Extension continues to the left but as Maginhawa Street in UP Teachers Village. The street on the right is also a part of a residential area, Bgy. Botocan, along which is the ROW of Meralco’s power transmission lines.

Fork in the road – V. Luna Extension continues to the left but as Maginhawa Street in UP Teachers Village. The street on the right is also a part of a residential area, Bgy. Botocan, along which is the ROW of Meralco’s power transmission lines.

–

CLRV: another look at the LPG Jeepney

The research on Customized Local Road Vehicles (CLRV) is currently underway with the project team going around the country to document different jeepney designs. The main objective of the study is to be able to formulate and recommend standards for jeepneys based on the requirements of stakeholders (e.g., passengers) and from the perspective of safety, ergonomics and efficiency. The last term is quite tricky as efficiency here generally refers to the performance of the vehicle, particularly related to fuel consumption. Efficiency may also touch on the capacity of the jeepneys, which would have implications on revenue (i.e., more passengers mean more fares).

Following are photos taken prior to the recent workshop held in Calamba, Laguna where the outcomes of previous workshops in Iloilo and Davao were presented for validation by a similar group of stakeholders. These included cooperatives, assemblers, automobile companies, NGOs, government agencies and other interested parties to the CLRV research. The study is being conducted under the auspices of the Philippine Council for Industry, Engineering and Energy Research and Development (PCIEERD) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) and funded by the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC).

One of the jeepneys on display was a 24-seater LPG-powered jeepney by David Motors

One of the jeepneys on display was a 24-seater LPG-powered jeepney by David Motors

Hyundai Theta engine converted for LPG

Hyundai Theta engine converted for LPG

Another look at the engine, which is practically the same engine used by the popular Starex vans. There were two other LPG jeepneys that day with both having Toyota engines converted for LPG. The engines are from the ones used by Hi-Ace models.

Another look at the engine, which is practically the same engine used by the popular Starex vans. There were two other LPG jeepneys that day with both having Toyota engines converted for LPG. The engines are from the ones used by Hi-Ace models.

Bench seats inside the LPG jeepney – there is still a door at the rear but it is used as an emergency exit rather than the main entry/exit for the vehicle. The sliding windows are sealed because of the air-conditioning installed for this jeepney.

Bench seats inside the LPG jeepney – there is still a door at the rear but it is used as an emergency exit rather than the main entry/exit for the vehicle. The sliding windows are sealed because of the air-conditioning installed for this jeepney.

The main door for the jeepney is at the right side just across from the driver. This design mimics those for buses and should enable more efficient collection of fares. That is, passengers may be asked to pay their fares immediately upon boarding the jeepney.

The main door for the jeepney is at the right side just across from the driver. This design mimics those for buses and should enable more efficient collection of fares. That is, passengers may be asked to pay their fares immediately upon boarding the jeepney.

6A close look at the dashboard, which is a mix of parts coming from different vehicles. The steering wheel, for example, bears the emblem of Hyundai. This jeepney had power features such as power windows that can be controlled by switches on the panel board to the left of the steering wheel.

6A close look at the dashboard, which is a mix of parts coming from different vehicles. The steering wheel, for example, bears the emblem of Hyundai. This jeepney had power features such as power windows that can be controlled by switches on the panel board to the left of the steering wheel.

Driver’s rear view of passengers and whatever will be trailing the jeepney in traffic.

Driver’s rear view of passengers and whatever will be trailing the jeepney in traffic.

The jeepney door is operated through a lever, parts of which are taken from a gear shift. The handle is well within reach of the driver of the vehicle.

The jeepney door is operated through a lever, parts of which are taken from a gear shift. The handle is well within reach of the driver of the vehicle.

Exec. Dir. Rowena Guevara of DOST-PCIEERD interviews the driver and mechanic of this LPG from David Motors. According to them, the performance of the jeepney is the same as conventional ones and that this less noisy as well as having less emissions. Assemblers of LPG jeepneys say that consumption is about 7.3 km/kg of LPG, which compares well with the estimated 7.5 km/L of diesel consumed by well-maintained conventional jeepneys. LPG is cheaper so it can be inferred that overall, drivers and operators would have increased revenues if they used LPG jeepneys.

Exec. Dir. Rowena Guevara of DOST-PCIEERD interviews the driver and mechanic of this LPG from David Motors. According to them, the performance of the jeepney is the same as conventional ones and that this less noisy as well as having less emissions. Assemblers of LPG jeepneys say that consumption is about 7.3 km/kg of LPG, which compares well with the estimated 7.5 km/L of diesel consumed by well-maintained conventional jeepneys. LPG is cheaper so it can be inferred that overall, drivers and operators would have increased revenues if they used LPG jeepneys.

The LPG jeepney is one (there are also electric jeepneys) of the variants being touted as the future of the vehicle. The “eco” tag is among the pitches for these jeepneys and should be a consideration for the study.

The LPG jeepney is one (there are also electric jeepneys) of the variants being touted as the future of the vehicle. The “eco” tag is among the pitches for these jeepneys and should be a consideration for the study.

–

Suitability of public NMT in the city?

Paratransit systems are a common thing all around the Philippines. Some have been part of the mainstream that to call them paratransit seems inappropriate. Among the most dominant modes of transport in the country are the jeepneys and motor tricycles that serve short to very long routes in many areas in the country including the National Capital Region. There is also the so-called kuliglig in the City of Manila that is a 3-wheeler comprised of a bicycle and a side car. The bicycle is motorized, using a small motor much like the one used by pumpboats or bancas. These are very much the same as the “tricyboats” of Davao City and other parts of Mindanao and the Visayas. The “original” kuliglig may be found in rural areas and these are basically farm tractors pulling carts that may be used to transport people or goods (e.g., farm products, raw materials, etc.).

When the term “non-motorized transport” or NMT is mentioned, the first things that come to mind are probably bicycles and walking. There are other NMT modes around including animal drawn vehicles and pedicabs. Perhaps the most well-known animal drawn vehicles in the Philippines are the calesas and caretelas, which are pulled by horses. Pedicabs are 3-wheeled vehicles consisting of a bicycle and a side car. These are quite popular in residential areas particularly in residential subdivisions or villages where tricycles have been prohibited or restricted due to their noise and emissions.

Pedicabs, however, have become an attractive means of livelihood for people who have less options for employment (i.e., many drivers have no qualifications to apply for more formal jobs). As such, one will find them proliferating where there is a perceived demand for them; including urban streets where they serve as feeder services quite similar to those offered by their motorized counterparts. While tolerated along minor streets, many have tested the waters and the limits of regulations by taking major roads. The following photos show such examples where pedicabs are seen operating along major roads.

NMT along national roads – pedicab at the intersection of Quezon Avenue and Agham Road

NMT along national roads – pedicab at the intersection of Quezon Avenue and Agham Road

Informal terminal for informal transport – pedicab queue along the Quezon Ave. service road

Informal terminal for informal transport – pedicab queue along the Quezon Ave. service road

Cause of congestion? – pedicab (and tricycle) operating along the bus lanes of EDSA in Pasay City. Such situations expose drivers and their passengers to risks of being hit by larger motorized vehicles such as buses and trucks.

Cause of congestion? – pedicab (and tricycle) operating along the bus lanes of EDSA in Pasay City. Such situations expose drivers and their passengers to risks of being hit by larger motorized vehicles such as buses and trucks.

Over-reaching? – pedicabs defy regulations against them using national roads and particularly major ones like EDSA.

Over-reaching? – pedicabs defy regulations against them using national roads and particularly major ones like EDSA.

There is the persistent challenge of how to rationalize public transportation in many Philippines cities. In fact, there are cities that have embraced paratransit modes as part of their character and thus seem unlikely to upgrade or phase out such transport modes from roads or routes that require higher capacity vehicles to deliver higher levels of service. For one, there are socio-economic and political factors that have to be considered in any initiative focusing on these modes of transport. Many are already organized or members of organizations such as tricycle operators and drivers associations (TODA) and jeepney operators and drivers associations (JODA). These have become quite influential over the years and have even participated in elections as party list groups while also exerting pressure on government agencies when issues like fuel price increases and fare setting are in the spotlight.

Many public NMTs are not as organized or empowered as their motorized counterparts. However, many are connected with groups such as those of the urban poor and NGOs taking their side when issues are raised regarding their operations. Perhaps these NGOs should take a closer look at public transport as not just a source of livelihood considering the responsibilities that come with providing such services. And perhaps they should also busy themselves with helping people learning skills that will not commit them and their descendants to being jeepney, tricycle or pedicab drivers.

–

Comparative study of jeepneys: LPG Jeepney

The University of the Philippines Diliman, through its National Engineering Center (NEC), National Center for Transportation Studies (NCTS) and the Department of Mechanical Engineering’s Vehicle Research and Testing Laboratory (VRTL), is conducting a comparative study on jeepneys. Three jeepneys will be the subject of road and laboratory tests including one conventional (diesel), one LPG, and an electric jeepney. The study is supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) through its Energy Utilization and Management Bureau (EUMB).

The following photos show the LPG jeepney provided by Pasang Masda that will be used for the study. Road tests will simulate actual operation along an actual jeepney route. The DOE secured permits from the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) for the deployment of the 3 jeepneys for the UP-North EDSA (SM) route. A similar permit was also secured from the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) for the jeepneys to be exempt from the number coding scheme.

LPG jeepney unit used in the study

LPG jeepney unit used in the study

The LPG jeepney provided by Pasang Masda was assembled by David Motors, the pioneer of the LPG jeepney, and is owned by the jeepney group’s leader himself, Ka Obet Martin.

The LPG jeepney provided by Pasang Masda was assembled by David Motors, the pioneer of the LPG jeepney, and is owned by the jeepney group’s leader himself, Ka Obet Martin.

NCTS and David Motors staff work on the LPG jeepney’s engine in preparation for road tests. All jeepneys must be in tip-top condition prior to the tests in order for the comparisons to be objective.

NCTS and David Motors staff work on the LPG jeepney’s engine in preparation for road tests. All jeepneys must be in tip-top condition prior to the tests in order for the comparisons to be objective.

A look at the LPG jeepney engine

A look at the LPG jeepney engine

The jeepney’s engine is supposedly not a converted one from a gasoline engine but is said to be an original Hyundai LPG engine.

The jeepney’s engine is supposedly not a converted one from a gasoline engine but is said to be an original Hyundai LPG engine.

The LPG engine needed some maintenance work as it was apparently not well-maintained according to David Motors’ staff.

The LPG engine needed some maintenance work as it was apparently not well-maintained according to David Motors’ staff.

Fuel indicator for the LPG jeepney

Fuel indicator for the LPG jeepney

It turned out that it wasn’t only the engine that needed some attention. David Motors staff had to check everything that may affect the performance of this jeepney unit.

It turned out that it wasn’t only the engine that needed some attention. David Motors staff had to check everything that may affect the performance of this jeepney unit.

9The brakes on this unit seemed to be defective; something that will affect the performance in both road and lab tests to be conducted.

9The brakes on this unit seemed to be defective; something that will affect the performance in both road and lab tests to be conducted.

As of this writing, the road and lab tests have not been conducted for the LPG jeepney due to the many issues about the unit provided by Pasang Masda. Apparently, the group was not doing its part in the study and it was as if they were passing on the costs of fixing the unit they provided to the study team. We hope it was not a conscious effort on their part, which if it did meant they were dealing with us in bad faith – not a good thing if they wanted to be a partner in this research collaboration.

–

Paratransit in Davao City

While visiting a jeepney assembler in Davao, we took the opportunity to take not a few photos of paratransit vehicles along one road in Davao City. Of particular interest to us were what appeared to be three-wheelers that resembled the tuktuks of Thailand and the four-wheeled multicabs that served as an intermediate mode with passenger capacities between that of the tricycle and the typical jeepney.

What at first seemed to be three-wheelers were actually four-wheeled vehicles. For propulsion, they used typical motorcycles but instead of one-wheeled sidecars like the typical tricycles found in many cities and towns across the country, the fabricated body has 2 wheels and provided for two benches to accommodate more passengers.

Following are photos of these 4-wheeled paratransit vehicles we took while visiting a jeepney assembly in Davao. While there is a basic form for each vehicle, there are actually some distinct features for each, probably the manufacturer’s or assembler’s signature. There is no distinct color for any particular route so commuters would have to check the panel information before flagging one to make sure whether the PUV serves their destination although these seem to have fixed routes.

Maroon body with white roof [Agdao – Jerome route]

Maroon body with white roof [Agdao – Jerome route]

Gold body and roof [Agdao – South Bay route]

Gold body and roof [Agdao – South Bay route]

Black body and yellow roof [Agdao – Jerome route]

Black body and yellow roof [Agdao – Jerome route]

Black body and blue roof [Agdao – South Bay route]

Black body and blue roof [Agdao – South Bay route]

Black body and white roof [Agdao – Jerome route]

Black body and white roof [Agdao – Jerome route]

We were also able to observe another form of jitney, which are generally called multicabs in the Philippines. The term multicab seem to have originated from a brand for these 3-cylinder engine vehicles that are fitted to carry passengers or in some cases as small freight vehicles. These are very popular in the Visayas and Mindanao where they typically seat 10 – 14 passengers excluding those in the front seat. The vehicle is narrower than the typical jeepney so only two people can usually fit in the front.

Typical jeepney design in Davao

Typical jeepney design in Davao

–