Home » Transport Planning (Page 3)

Category Archives: Transport Planning

Planning for True Transportation Affordability: Beyond Common Misconceptions

How much do we spend on transportation as part of our budgets? Is it 5% of your monthly budget? Is it 10%? Or is it eating up a substantial part of what you’re earning?

Source: Planning for True Transportation Affordability: Beyond Common Misconceptions

To quote from the article:

“This research indicates that many common policies favor expensive transportation and housing over lower-cost alternatives, which drives the cost of living beyond what is affordable, leaving too little money to purchase other necessities. The result is immiseration: growing stress, unhappiness, and discontent.

The solution is simple: planning should favor affordable over expensive modes and compact development over sprawl. This is not to suggest that automobile travel is bad and should be eliminated. Many people are justifiably proud of being able to afford a nice car, and automobiles are the most efficient option for some trips. However, automobile travel requires far more resources and is far more expensive than other modes, typically by an order of magnitude, so true affordability requires an efficient, multimodal transportation system that allows travelers to choose the options that truly reflect their needs and preferences.

Affordability requires a new economic paradigm; rather than trying to increase incomes or subsidies we need to increase affordability and efficiency so households can satisfy their basic needs consuming fewer resources and spending less money. Our planning should be guided by a new goal: how can we help families be poor but happy.”

I share this article because it provides a more complete narrative and assessment than those just focusing on transport. Home choice locations and affordable housing are part of the equation. Looking at transport alone can be myopic and leads us to think it is the only problem to solve.

–

Are transportation issues election issues in the Philippines?

Are transportation issues in the Philippines? Or are these issues at the local level? Here is an article about how transportation issues were brought to light and were actual topics in the ballot in Los Angele, California in the US:

Tu, M. (November 25, 2024 ) “Bike, Bus and Pedestrian Improvements Won the Vote in L.A. How Did Advocates Pull It Off? “ Next City, https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/bike-bus-pedestrian-improvements-healthy-streets-los-angeles-ballot?utm_source=Next+City+Newsletter&utm_campaign=532838ef65-DailyNL_2024_11_18_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_fcee5bf7a0-532838ef65-44383929 [Last accessed: 11/26/2024]

The three lessons in the article are:

- Build a coalition – “In the lead-up to the election in March, Streets For All successfully secured endorsements from unions, climate organizations and business groups that saw the vision for safer streets.”

- Safety wins – “We could make climate arguments, we could make equity arguments, but the thing that felt the most bulletproof to us and the most empathetic to the general Angeleno was just road safety,”

- Keep it simple – “…simple messages were the most effective. Vredevoogd fought for one billboard on Vermont Avenue that read “In 2022, more pedestrians died on Vermont Avenue than in the state of Vermont.”

Los Angeles or LA as many people fondly call the city is well known for being car-centric (as opposed to San Francisco to the north, which is more transit-oriented). Perhaps we can learn from this experience though I know there are already groups and coalitions lobbying for better transportation in the Philippines. Are they successful and to what extent are they succeeding? Granted there are different situations and conditions, even modalities, to engage politicians, there are also so-called party list groups claiming to represent the transport sector but none appear to be really standing up for issues like improving public transport or road safety. And so the challenge is still there for people to make transportation issues election issues in the country.

–

On the future of transportation – some history lessons

I found this interesting article that basically is a history lesson on transportation systems and infrastructure:

Dillard, G. (October 21, 2024) “Our infrastructure is Not Our Destiny,” Medium.com, https://medium.com/the-new-climate/our-infrastructure-is-not-our-destiny-6d7f8355144a [Last accessed: 11/17/2024]

To quote from the article:

“We’ll never build out a network of electric-car charging stations, they say, or How could we possibly replace all of these highways with mass transit? But the infrastructure that dominates our world today once seemed impossible, until it didn’t…

As we begin to imagine a new way of organizing our economy, let’s remember that infrastructure isn’t destiny, nor is it forever. Today, our fossil-fuel present may feel like the only “practical” way to do things — just as the canals, and then the railroads, once felt like the only possibility.

So the next time a transition away from cars, fossil fuels, and the other technologies that dominate our world seems impossible, think about Hermon Bronson and Robert Fulton, who surely thought that canals were the infrastructure of the future. They were wrong, and so are the people who tell us that it’s impossible or impractical to build a greener world.”

Perhaps we can take a look at our transportation infrastructure development history and the way it’s going now. It would be good to contextualize all those planned tollways and inter-island bridges against what is really most urgent these days (i.e., mass transit, active transport for our rapidly growing cities). I’ve always stated here about how some infra are nice to have but aren’t as urgent as others that need more push and support and will be utilized by and benefit more than fewer people.

–

On the general benefits of public transportation

Here’s another good read that has links to the outcomes of studies pertaining to public transportation’s direct and indirect effects on vehicle miles traveled or VMT (in our case we use vehicle kilometers traveled or VKT):

McCahill, C. (November 12, 2024) “The benefits of transit extend well beyond transit riders,” State Smart Transportation Initiative, https://ssti.us/2024/11/12/the-benefits-of-transit-extend-well-beyond-transit-riders/ [Last accessed: 11/20/2024]

To quote from the article:

“…good transit has a ripple effect on land use and travel behavior. For every mile not driven by transit riders, transit accounts for another six to nine miles not driven among the larger population. “

Note the potential reduction in VKT’s attributed to mass transportation or transit.

–

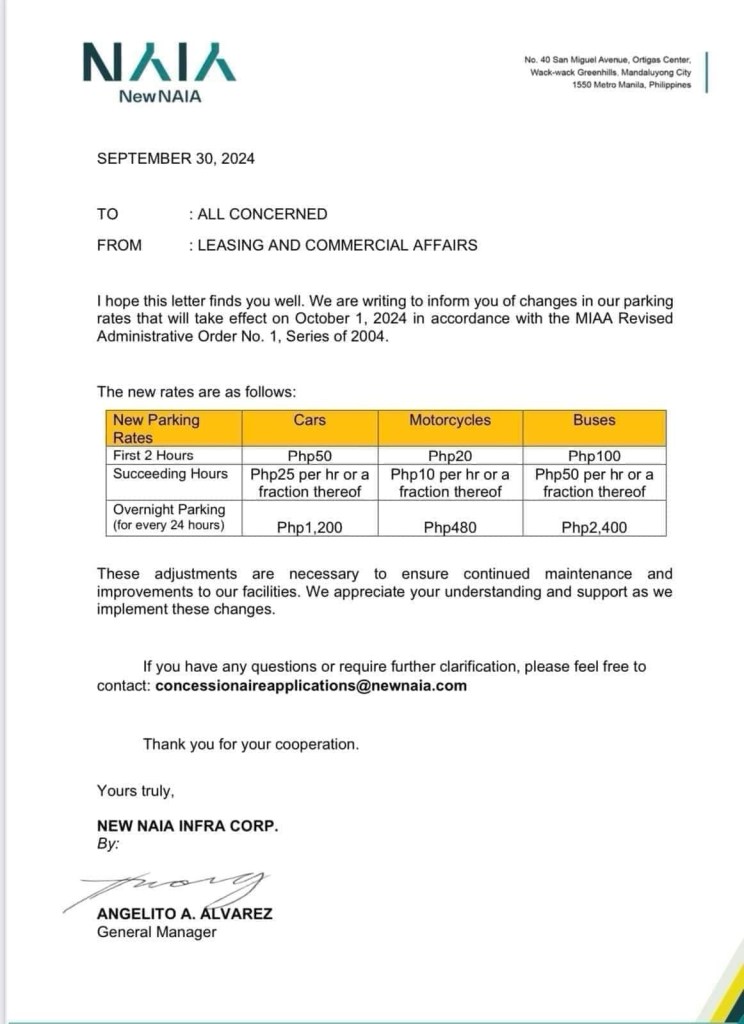

Increase in parking rates at NAIA

A friend shared this notice about the increase in parking rates at NAIA.

Parking at any of the terminals has been quite difficult if not horrendous. Everyone seems to be bringing their car to the airport for pick up and drop offs as well as leaving them for a night or more while traveling abroad or somewhere in the country. And then there are those who park there because the rates are supposed to be cheaper than the hotels and mall around the airport (e.g., the case of Terminal 3). Will the increase in the rates discourage unwanted or unnecessary parking? Perhaps not because people are still quite dependent on cars as their primary mode in and out of NAIA.

Access to the airport remains road-dependent. Granted there are many options like ride hailing, airport bus and taxis, these are all road based. They share the same roads that are often congested. The tollways are not enough to ease traffic in the area, which aside from airport generated trips include those from offices and industries in the area.

Too long has the need for a rail access for the terminals and government has failed to provide it. It would at least have engaged private sector for this provision but it took so long. Perhaps the Metro Manila subway will change that but we have to wait a long while to find out.

–

On transportation and global health – article share

I was supposed to write about the keynote lecture delivered during the 30th Annual Conference of the Transportation Science Society of the Philippines (TSSP). I am sharing instead an article written by Dr. Renzo Guinto who is an Associate Professor at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute based at the National University of Singapore.

Here is the link to his article on the Philippine Daily Inquirer: Health at the center of transport and mobility

I will not quote from the article and leave it to my readers to read and appreciate the articles content.

–

Technical sessions at the TSSP 2024 Conference

I am sharing here the latest draft of the technical sessions for the 30th Annual Conference of the Transportation Science Society of the Philippines (TSSP). The conference will be held in Iloilo City this coming September 13, 2024.

I will share the draft program for the morning plenary session in the next post.

–

SPRINT principles for bicycles

Here is the link to how to improve your city’s or municipality’s bicycle facilities based on scores guided by the SPRINT principles: https://cityratings.peopleforbikes.org/create-great-places

SPRINT stands for:

S -Safe Speeds

P-Protected Bike Lanes

R-Reallocated Space

I-Intersection Treatments

N-Network Connections

T-Trusted Data

The site provides links and examples of good practices of actual bike projects in the US. Many of these can be replicated or adapted to Philippine conditions. These are something that the active transport section of the Department of Transportation (DOTr) should look into and perhaps provide a reference for developing and improving bicycle facilities in the country.

–

On a ‘tipping point’ for bikeability in cities

Here’s a nice article on bikeability and pertains to cities in the United States that developed bikeways or bike lanes during the pandemic. Like many cities that have ‘discovered’ cycling as a viable mode of transport particularly for commuting during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is postulated that there would be a threshold when people would switch to cycling and/or demand for more cycling facilities.

Wilson, K. (June 25, 2024) “Has Your City Passed the ‘Bikeability Tipping Point’?,” StreetsBlog USA, https://usa.streetsblog.org/2024/06/25/has-your-city-passed-the-bikeability-tipping-point [Last accessed: 7/2/2024]

To quote from the article:

“A whopping 183 American communities achieved a score of 50 or higher on PeopleForBikes annual City Ratings this year, up from just 33 in 2019. The means 183 communities have scored at least half of the available points on the group’s signature “SPRINT” rubric that includes such measures as protected bike lanes, safe intersection treatments, and reduced speed limits that are unlikely to kill a cyclist in the event of a crash, among other factors.

And when a city clears that 50-point threshold, the authors of the ratings say that its local bike culture has firmly taken root — and that every new roadway improvement will inspire more improvements, rather than a fierce fight against a car-dominated status quo.

“Once you’ve hit 50, your city probably has a pretty good low-stress bike network,” said Martina Haggerty, the senior director of local innovation at PeopleForBikes. “[That’s] not to say that there aren’t still improvements to be made [but it] probably means that more people are riding bikes in those communities because they feel safe and comfortable. And when more people start riding bikes, those people tend to become advocates for better bike infrastructure and for pro-bike policies, which, [in turn,] will get more people riding.”

There are many links found in the article itself that are “click worthy”. I recommend the reader to explore the rubric from PeopleForBikes and see for yourself how this can be adopted for your city. Is such a rubric applicable to the Philippines? Perhaps, but there would be a need to assess the the situation in each city or municipality. So far, there have been mixed reviews among cities, especially those that appeared to have been more progressive and were more aggressive than others in putting up bicycle facilities including bike lanes. Perhaps the rubric can be applied to see how our LGUs measure up?

–

On BRT being the solution to many cities’ public transport problems

Here is a very informative article about the benefits of a bus rapid transit (BRT) to a city:

Renn, A.M. (June 17, 2024) “The Bus Lines That Can Solve a Bunch of Urban Problems,” Governing, https://www.governing.com/transportation/the-bus-lines-that-can-solve-a-bunch-of-urban-problems [Last accessed: 6/25/2024]

To quote from the article:

“One benefit of BRT is that it is much more capital-efficient and faster to implement than light rail. For many years, urban advocates have promoted light rail over bus transit, impressed by the success of light rail systems such as the one in Portland, Ore. But today’s light rail lines are extremely expensive. One proposed in Austin, Texas, for example, is projected to cost $500 million per mile. Also, most of the cities that have desired light rail are low-density cities built around cars and with little history of extensive public transit ridership. Converting them to transit-oriented cities would be a heavy lift.

BRT is much cheaper. The 13-mile Red Line BRT in Indianapolis, opened in 2019, cost less than $100 million — not per mile, but in total. The much lower financial lift required for building bus rapid transit makes it more feasible for cities to raise the required funds.

Because they typically run on city streets, BRT systems also offer the chance to perform badly needed street and sewer repairs during construction. Sidewalks can be rebuilt or added. Traffic signals can be replaced, along with new features such as prioritizing buses over auto traffic and additional pedestrian safety measures. The reduction of traffic lanes itself is sometimes a worthwhile street redesign project.”

It’s been more than a decade (almost 2 decades to be more accurate) since a BRT was proposed in Cebu City and in Metro Manila. So far, there is still none operating in the Philippines. The EDSA Carousel probably wants to be one but is far from being a BRT based on operations and performance. Cebu’s is supposed to be currently in implementation but it seems Davao might just beat them to it with its high priority bus project. The Philippines requires a proof of concept of the BRT in one of its cities that could be the inspiration for similar projects in other cities especially those that are already highly urbanized.

–