Home » Public Transport » Paratransit (Page 7)

Category Archives: Paratransit

Harbinger of change for public transport?

Comets have been viewed as signs, omens or harbingers of something that will happen. I like the word “harbinger” more than “omen.” It brings about a certain mystery to it that does not necessarily imply something bad or evil. In this case, the comet is a vehicle and “Comet” stands for City Optimized Managed Electric Transport, an electric jitney that is being touted as a replacement for the ubiquitous jeepney that has evolved from its WW2 ancestor. It does have the potential of being a game changer if there is an enabling environment for it and if (a big “if”) it addresses fundamental issues with electric vehicles such as those that are technical (battery life, range, speed, etc.), pertaining to after sales (maintenance, technical support) and operational (suitable routes, fares, charging stations, etc.).

[All photos taken by Engr. Sheila Javier of the National Center for Transportation Studies]

Prototype Comet at the NCTS parking lot – notice that it is larger than the AUV on the other side of the vehicle. The Comet will utilize a tap card for fares, similar to the card that is proposed for use in the Automated Fare Collection System for the LRT/MRT system.

Prototype Comet at the NCTS parking lot – notice that it is larger than the AUV on the other side of the vehicle. The Comet will utilize a tap card for fares, similar to the card that is proposed for use in the Automated Fare Collection System for the LRT/MRT system.

Inside the vehicle, one immediately gets a feeling of space. In fact, a person can stand inside the vehicle unlike the case of jeepneys where people need to bend so as not to bump their heads at the ceiling.

Inside the vehicle, one immediately gets a feeling of space. In fact, a person can stand inside the vehicle unlike the case of jeepneys where people need to bend so as not to bump their heads at the ceiling.

The vehicle has a side entrance and exit unlike the rear doors of typical jeepneys.

The vehicle has a side entrance and exit unlike the rear doors of typical jeepneys.

The Comet looks like a mini-bus from behind. Proponents have stated that drivers will be trained for road safety as well as operations for designated stops and scheduled services.

The Comet looks like a mini-bus from behind. Proponents have stated that drivers will be trained for road safety as well as operations for designated stops and scheduled services.

The Comet is being touted as a replacement for the jeepney and is being promoted via an initial route that would connect SM Megamall in Ortigas Center, Pasig City to SM City North EDSA in Quezon City. The route will be counter-clockwise from SM Megamall to SM North EDSA via Circumferential Road 5 including E. Rodriguez Avenue and Katipunan Avenue, UP Diliman, Commonwealth Avenue, Elliptical Road and North Avenue. From SM North to SM Megamall, it will take EDSA. While I am not sure if the Comet has been granted a franchise and how many units they can deploy, this proposed route will overlap with existing jeepney and bus routes including direct competition with UP-Katipunan and UP-North EDSA routes, and buses plying routes that cover the stretch from North EDSA to Ortigas Center. I think that this route is mainly for publicity considering there are probably other, more suitable routes for the Comet. It has not been subject to rigorous tests (just like the e-jeepneys before it), which is not a good thing, considering the experiences of the e-tricycle in Taguig and the e-jeepneys in Makati. Hopefully, they have learned the lessons from these past efforts and that they already have the answers hounding EVs as applied to public transport.

–

From FX to UV Express – a story of evolution

For those not familiar with its evolution, the UV Express has an interesting history. It started as a contracted taxi service utilizing the new Asian Utility Vehicle (AUV) model released by Toyota that they called the FX (The same model is known as the Kijang in Indonesia.). I can say that I witnessed the birth of FX services in the 1990s when taxis were approached by commuters having common destinations. I was among those who were desperate enough to get home and tired of getting into those long lines of people waiting for jeepneys in Cubao. The lines were not all that bad though as it used to be worse when people had to box out one another to board a jeepney as they arrived near Ali Mall.

Taxis had the advantage of not having fixed routes so they could bypass congested road sections. They could take alternate routes that despite covering longer distances, incurred shorter travel times. Passengers negotiated with the drivers for a common destination and a fare that’s typically higher than what would be charged if the meter was used. I remember that there were times when passengers (like me) negotiated with the driver with the dare to run the meter just to prove that he’d be better off with the money we would be paying rather than wait for regular fares. Of course, this practice of negotiating was illegal as taxis in Metro Manila were metered. But passengers were quick to help out the cabbie in case he gets caught, with everyone claiming that he or she knew the others and that they were traveling as a group. One use of a running meter was that they were a group paying regular fare.

Taxi operators and drivers quickly caught on to the idea and many eventually became enterprising. These were mostly FX drivers who could carry 5 to 7 passengers depending on the seat configuration for the vehicles. Toyota took full advantage of government incentives for AUVs by introducing what was claimed to be 10 seater vehicles, maximizing space at the middle and rear to seat a total of 8 people in addition to 2 in the front. This also translated into a maximization of revenue per load of 10 people and soon, “standard” fares were being established for certain routes like Cubao-Cainta Junction, which I remember cost 20PhP per person regardless of whether you were alighting before Cainta Junction. Eventually, issues were raised regarding their operations as contracted vehicles as they were still classified as metered taxis and should have not refused single or few passengers. There were also issues regarding their competing directly with jeepneys as some FX plied routes similar to jeepneys especially when traffic was more manageable. Eventually, the DOTC and the LTFRB moved to regulate this emergent transport service and formalized (fixed) routes and franchises rather than retain their flexibilities like taxis. In effect they became express shuttle services and fares and rules were also set accordingly, also to protect the interests of the riding public.

Toyota Revo AUV UV Express vehicle plying the Pasig-Ayala Center route

Toyota Revo AUV UV Express vehicle plying the Pasig-Ayala Center route

It became known as Garage to Terminal (GT) Express during the last administration. There was a joke then that the term used was according to the nickname of the then Chairman of the LTFRB. It’s name again was changed into Utility Vehicle (UV) Express after the change in administration.

Nissan Urvan van UV Express at the Puregold at the NLEX Valenzuela Exit

Nissan Urvan van UV Express at the Puregold at the NLEX Valenzuela Exit

UV Express now proliferate around Mega Manila and come in different vehicle types and sizes. Most are AUV’s like the Toyota Revo, Isuzu Crosswind or Mitsubishi Adventure. There are also vans like the Toyota Hi-Ace and Nissan Urvan. But there are also custom made vehicles like those utilizing the Mitsubishi L300 prime mover and fitted with a cab that seats 14 to 16 passengers. The latter types have capacities similar to jeepneys and airconditioning is somewhat weaker compared to the legit AUVs and vans. I think the UV Express vehicles are here to stay and they do serve a certain segment of commuters. However, while I also think their numbers are excessive (and government through the LTFRB needs to address this) there is really not much to argue about if more efficient and higher capacity and good quality transit systems cannot be realized in our cities. People deserve options for commuting and for those taking public transport, these UV Express services provide good quality transport that they are willing to pay for. Many of these services might just meet a natural death or decline once a better transport system is in place along main corridors but that seems a long way off from now given continued failures in mass transit project implementation.

–

Back in Bangkok

Back in Bangkok after a year, it was good that we are staying in the Siam Square area where I have become familiar with in the last decade when I seemed to be in Bangkok at least twice a year for official and personal trips. As we took the expressway en route to the city, I took a few shots from the perspective of a passenger of a van traveling along the elevated expressway.

Our hosts arranged transport between the airport and our hotel. This was in the form of a van, with which we traveled to the city via the expressway.

Our hosts arranged transport between the airport and our hotel. This was in the form of a van, with which we traveled to the city via the expressway.

The elevated expressway connecting the airport to the city center is impressive for its capacity. The photo above shows a section with at least 4 lanes and shoulder space. Personally, I could have taken the express rail transit that connects with the BTS Skytrain. The elevated airport railway line is seen along the right side of the expressway in the photo.

The elevated expressway connecting the airport to the city center is impressive for its capacity. The photo above shows a section with at least 4 lanes and shoulder space. Personally, I could have taken the express rail transit that connects with the BTS Skytrain. The elevated airport railway line is seen along the right side of the expressway in the photo.

This time around, I’d like to be able to some photos of street scenes in the city. Of course, that includes pictures of paratransit modes like the tuktuk and their motorcycle taxis. Here’s a couple of sample photos of tuktuks I took near our hotel.

Tuktuk running along a city street.

Tuktuk running along a city street.

More on Bangkok transport and traffic in the next posts!

Mini-bus

Walking to our meeting venue, I saw this small bus stopped at an intersection. I remembered a similar bus that we rode between the JR Shibuya Station and the Philippine Embassy in Nanpeidai (in the Shibuya District) in the late 1990s. The mini-bus is a form of paratransit that’s right there with the jitneys and van services that provide mainly short distance public transport services in, among others, city centers and residential areas.

The fare is fixed at 100 JPY and you can use your Suica or Pasmo card to pay your fare. Something like this could be suitable for CBDs in the Philippines including the Makati CBD, Ortigas CBD and maybe the future Quezon City CBD that is being developed in the north triangle area of that city. Other city centers where this mini-bus can be used are those in Cebu, Davao, Iloilo and Bacolod. Perhaps most desirable are low emission versions of this vehicle including, if available, electric buses. At present, Makati has electric jeepneys plying 3 routes along city roads in the Makati CBD. These will complement regular bus or rail services and should replace jeepneys along specific routes.

–

Pedicab fares

Tricycle and pedicab fares are set quite variably depending on the service areas and those regulating the services. In many cases, it is the pedicab association comprised of drivers-operators who set the fares, which are then supposed to be approved by local officials like those in the barangay or municipal/city hall. I say “supposed” here since most rates are not formally regulated in the manner like how the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) sets fares for buses, jeepneys and taxis. While the principles of “willingness to pay” is applied to some extent, pedicab and tricycle fares are usually imposed (to use a strong word) by tricycle and pedicab associations with very rough estimates of operating costs or, in the case of NMTs, the equivalent of physical effort, required to convey people.

In residential subdivisions or villages, associations may have a say in the fare rates. Where I live, the association sets the standard rates and these go to the extent of differentiating between day time and night time rates. There is even a rate for when streets are flooded! There is also a definition for regular and special trips and rates are according to the general distance traveled by pedicab. That is, fares to Phase 2 are generally higher than those for Phases 1 and 3 because Phase 2 streets are generally farther from the reference origin/destination, which is the village gate. Given the effort of pedicab drivers to transport passengers, I think the rates are just right. The only part there that seems unusual is the rate of PhP 1/minute for waiting time, which to me seems to high. Nevertheless, there is nothing to stop passengers from showing their appreciation for hard work in the form of tips. And there is no limit to the generosity of some passengers who choose to pay more to the (pedi)cabbie.

Tariff sheet displayed inside the sidecar of every pedicab of our village. The information is useful especially to guests or visitors who are not familiar with pedicab rates in the area.

Tariff sheet displayed inside the sidecar of every pedicab of our village. The information is useful especially to guests or visitors who are not familiar with pedicab rates in the area.

–

Tricycles in the Philippines – Part 1

We start the “ber” months strong with an initial feature on an ubiquitous mode of transport in the Philippines. While the jeepney seems to have had most of the attention when the subject of public transport in the Philippines is discussed, the truth is that there is arguably another, more dominant mode of public transport in the country. These are the tricycles, a motorized three-wheeler consisting of a motorcycle and a sidecar. You see these everywhere around the country in most cities and municipalities where they thrive particularly in residential areas. They are usually the only mode of public transport for most people in rural areas where local roads are typically narrow. In many cases the only roads connecting communities may be national roads. And so, there is really no other choice for tricycles but to travel along national roads and against existing laws prohibiting tricycles from these roads.

Tricycle along the motorcycle lane of Circumferential Road 5

Tricycle along the motorcycle lane of Circumferential Road 5

Tricycles racing along the Olongapo-Castillejos Road in Zambales

Tricycles racing along the Olongapo-Castillejos Road in Zambales

Tricycle along Romulo Highway, Tarlac

Tricycle along Romulo Highway, Tarlac

Tricycles along Catolico Avenue in Gen. Santos City

Tricycles along Catolico Avenue in Gen. Santos City

Unlike buses and jeepneys, tricycles are not regulated under the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB). Instead, they are under the local government units that through one office or another issue the equivalent of franchises for tricycles to operate legally. Fares are quite variable but are usually according to distance though there are special rates for when passengers want to have the vehicle for themselves much like a taxi.

Unfortunately, few LGUs have the capacity to determine the optimum number of tricycles for service areas under their jurisdictions. As tricycle operations are often the source of livelihood for many, the granting of franchises is often seen as a way for mayors to have influence over people who would have “utang na loob” (debt of gratitude) for being granted franchises. The tendency, therefore, is to have too many tricycles as mayors try to accommodate more applicants who seem to have no other options to earn income or to invest in. This poses a challenge to many who want to reform the system and modernize or upgrade public transport in cities around the country.

–

Some thoughts on the issues on bus bans and terminals in Metro Manila

I had originally wanted to use “Clarifying issues on bus bans and terminals in Metro Manila” as the title for this post. However, I felt it was too strong a title, and one that would be more appropriate for a government agency like the MMDA or DOTC, or an LGU like Manila. More than fault-finding and criticizing government agencies and local governments, I believe we should take a closer and more objective look at the issues (or non issues?) pertaining to the Manila bus ban and the opening of the southwest provincial bus terminal for Cavite-bound buses. Following are my comments on issues raised the past weeks about the two initiatives.

Issue 1: There were no or few announcements about the implementation of the bus ban in Manila and the southwest terminal in Cavite.

Comments: While the bus ban in Manila came as a surprise to many, the move was actually a consequence of a Manila City Council resolution. Normally, such resolutions would take time to implement and would entail announcements for stakeholders. Though we will probably never know the truth or who is saying the truth about the resolution and its implementation, it is likely that bus operators already knew about the implications but decided to call Manila’s bluff and play the media and public appeal cards rather than comply with Manila’s requirements for franchised buses and terminals as they have done before in other issues like fuel prices and fare hikes.

I find it difficult to believe that the MMDA did not do its part in announcing the opening of the southwest terminal. Perhaps people thought the announcement was over a very short period? Or maybe people didn’t mind the announcement and are also at fault for paying no or little attention to the announcement? If so, then the public is also partly to blame for disregarding the announcement from the MMDA, assuming the agency won’t push through with its initiatives to implement central terminals for buses. Next up will be another southern terminal at Alabang and a northern one near Trinoma.

Issue 2: Poor transfer facilities and services including a lack of pedestrian facilities between the bus terminal and transfer point, and lack of public transport like jeepneys to ferry passengers to their destinations.

Comments: I think it’s quite clear that the MMDA and LGUs are at fault here. Despite the construction and scheduled opening of the southwest terminal, there have been limited effort in improving pedestrian facilities. Such facilities needed to be in place prior to or upon the opening of the southwest terminal and requiring all provincial buses to terminate at the facility instead of continuing to Metro Manila. People-friendly facilities could have helped people in adjusting to the new policy though walking from 100 to 200 meters is certainly not for all, especially during this rainy season. Senior citizens and persons with disabilities (PWDs) would have specific needs that could have been addressed from day one of operation of the terminal. One approach to “bridge the gap” between the terminal and where people could take city bus and jeepney rides could have been to modify some city bus and jeepney routes to make these closer to the terminal. Ideally, the terminal could have been an intermodal facility providing efficient, seamless transfers between modes of transport.

In the case of Manila, the jeepneys were already there with routes overlapping with buses but their numbers and capacity could not cope with the demand from the buses. Since the main objective of Manila was to weed out colorum buses, it could have coordinated with the LTFRB to check the registration and franchises of buses rather than generalizing among all buses. Perhaps Manila just wanted to make a big statement? But then this was at the expense of the riding public, which obviously got the attention of many including the media. Coordination among agencies and LGUs, however, has not been a strong suit for these agencies, and this thought leads us to the next issue.

Issue 3: Lack of coordination among LGUs and agencies in implementing transport schemes.

Comments: This issue is an enduring one and has been the topic of discussions, arguments and various fora for as long as we can remember. On one hand, the DOTC and the LTFRB should provide guidelines and guidance to local governments on transport planning and services. The agencies should be proactive in their engagement of LGUs in order to optimize transport services under the jurisdiction of national agencies and local governments. On the other hand, LGUs must accept the fact that most if not all of them are ill equipped or do not have the capacity nor capability to do transport planning much less addressing issues regarding public transport. Citing the Local Government Code and its devolution of local transport to LGUs everytime there’s a transport issue certainly won’t help LGUs solve their problems.

Issue 4: Terminals required for city buses in Manila.

Comments: There should be a terminal for city buses in Manila but not a terminal for each company. There should only be one or maybe two terminals where buses can make stops prior to making the turnaround for the return trip. There is actually a terminal in Manila, which the city can start with for city buses. This is the one just beside the Metropolitan Theater and near City Hall, which can be utilized by city buses. It is also close to the LRT Line 1 Central Station so the facility can be developed as a good intermodal terminal for land transport.

Issue 5: Colorum or illegal public transport vehicles in Manila

Comments: This is actually a problem not just for Manila but for the rest of Metropolitan Manila and the rest of the country. The colorum problem is there for both conventional and paratransit services as there are illegal buses, jeepneys, UV express, multicabs, taxis, tricycles and pedicabs everywhere. Many of these are allegedly being tolerated by national agencies and local governments with many allegedly being fielded or owned by public transport operators themselves.

–

In most cases, the best time to evaluate a traffic policy or scheme is NOT during its first days or weeks of implementation but after a significant time, say at least a month, after it was implemented. This is because the stakeholders, the people involved would take some time to adjust to any scheme or policy being implemented. This adjustment period will vary according to the magnitude or scope of the scheme/policy and can be quite “painful” to many who have gotten used to the old ways. Usually, a lot of comments and criticisms are quite emotional but it is clear that the collective sentiment is the result years or decades of poor transport services and fumbling by government agencies. Transport in Metro Manila is already quite complicated with routes overlapping and services competing with each other for the same passengers. Perhaps it is time to simplify transport while also in the process of optimizing and rationalizing services. I have written about this in this previous post.

More transport issues in Manila will come about should the city train its attention on other modes of transport including jeepneys, UV express vehicles, tricycles, pedicabs and kuligligs. If the city is really intent on reforming transport services within its jurisdiction, it should consider the needs of all stakeholders and especially and particularly the riding public. Transport should be inclusive, people-friendly as well as environment-friendly and there are many good practices in other cities that Manila could refer to and study for adaption and adoption for the city. If it is successful in improving transport, then perhaps Manila could be the country’s model for transformation from being the “Gates of Hell” to being a “Portal to Heaven” to residents and visitors alike.

–

What is the context for electric tricycles in the Philippines?

The NEDA Board recently approved six projects that included one that will be promoting electric vehicles throughout the country. Entitled “Market Transformation through Introduction of Energy Efficient Electric Vehicles Project” (formerly Market Transformation through Introduction of Energy Efficient Electric Tricycle (E-Trike) Project), the endeavor seeks to replace thousands of existing conventional motorized 3-wheelers (tricycles) with e-trikes and to develop and deploy charging stations for these vehicles. While I have nothing against electric vehicles and have supported their promotion for use in public transport, I am a bit worried about the context by which electric tricycles are being peddled especially the part about equating “transformation” with “replacement.”

First, it is a technology push for an innovation that has not been fully and satisfactorily tested in Philippine conditions. The deployment of e-trikes in Bonifacio Global City is practically a failure and a mode that was not suitable from the start for the area it was supposed to serve (i.e., while there were already jeepneys serving the area, there were also the Fort Bus services and plans for a BRT linking the Ayala CBD and BGC. There are now few (rare sightings) of these e-trikes remaining at the Fort, as most of these vehicles are no longer functioning due to problems regarding the batteries, motors, and issues regarding maintenance. Meanwhile, the e-trikes in Mandaluyong, a more recent model, have also been difficult to maintain with one case reportedly needing the unit to be sent back to China for repairs.

Second, the e-trikes are a whole new animal (or mode of transport). I have pointed out in the past including in one ADB forum that the 6 to 8 seater e-trike model is basically a new type of paratransit. Their larger capacities mean one unit is not equivalent to one of the current models of conventional tricycles (i.e., the ones you find in most city and municipality around the country). Thus, replacement should not be “1 e-trike : 1 tricycle” but perhaps “1:2” (or even “1:3” in some cases). This issue has not been resolved as the e-trike units continue to be marketed as a one to one replacement for conventional trikes. There should be guidelines on this that local government units can use, particularly for adjusting the number of franchises or authorized tricycles in their respective jurisdictions. Will such come from the Department of Energy (DOE)? Or is this something that should emanate from Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC)? Obviously, the last thing we like to see would be cities like Cabanatuan, Tarlac or Dagupan having so many e-trikes running around after they have replaced the conventional ones, and causing congestion in the cities. Emissions from the tricycle may have been reduced but emissions from other vehicles should be significant due to the congestion.

Third, the proliferation of e-trikes will tie our cities and municipalities to tricycles. Many cities already and definitely need to upgrade their public transport systems (e.g., tricycles to jeepneys or jeepneys to buses, and so on). Simply replacing tricycles with electric powered ones does not effect “true” transformation from the transport perspective. Is the objective of transformation mainly from the standpoint of energy? If so, then there is something amiss with the project as it does not and cannot address the transport, traffic and social aspects of the service provided by tricycles (and other modes of transport).

So what is the context for the e-trikes or conventional tricycles? They are not even under the purview of the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) as they are regulated by LGUs. Shouldn’t the DOTC or the LTFRB be involved in this endeavor? Shouldn’t these agencies be consulted with the formulation of a framework or guidelines for rationalizing and optimizing transport in our cities? These are questions that should be answered by the proponents of this project and questions that should not be left to chance or uncertainty in so far as the ultimate objective is supposed to be to improve transport in the country. I have no doubt that the e-trikes have the potential to improve air quality and perhaps the also the commuting experience for many people. I have worries, however, that its promise will not be kept especially in light of energy supply issues that our country is still struggling with and deserves the attention of the DOE more than the e-trikes they are peddling.

–

Rizal Avenue – Part 2: Tayuman to Pampanga Street

In the last post on Rizal Avenue, the featured photos show conditions under the LRT Line 1, which included visual evidence of certain issues like on-street parking, poor lighting and even sanitation (i.e., garbage) along the corridor. This post features more of the same and perhaps worse in some cases that are used as proof of the blight caused in part by the LRT superstructure. I say in part because LRT Line 1 is not wholly to blame for problems under and around it. Local governments and the private sector share responsibility for the decline of the areas within the direct influence of the rail line. Napabayaan. But of course, this does not absolve proponents of the LRT Line 1 for poor station design.

Approach to Tayuman Station along the northbound side of Rizal Avenue.

Approach to Tayuman Station along the northbound side of Rizal Avenue.

Tayuman Station – shown in the upper part of the photo is one end of the northbound platform.

Tayuman Station – shown in the upper part of the photo is one end of the northbound platform.

Underneath the station, jeepneys clog the lanes as they load/unload passengers. LRT Line 1 stations are poorly designed for intermodal transfers (e.g., LRT to jeepney, LRT to bus, etc.).

Underneath the station, jeepneys clog the lanes as they load/unload passengers. LRT Line 1 stations are poorly designed for intermodal transfers (e.g., LRT to jeepney, LRT to bus, etc.).

Tayuman Road is a busy street in Manila that’s served by jeepneys connecting to major streets like Lacson Avenue to the east and Abad Santos and Juan Luna to the west. The photo shows a view to the east of the LRT Tayuman Station.

Tayuman Road is a busy street in Manila that’s served by jeepneys connecting to major streets like Lacson Avenue to the east and Abad Santos and Juan Luna to the west. The photo shows a view to the east of the LRT Tayuman Station.

Approach to the junction with Herrera Street

Approach to the junction with Herrera Street

Approach to Blumentritt Station – the station is named after Ferdinand Blumentritt, an Austrian who was a close friend of the national hero Jose Rizal. The street leads to a large public market close to the station (near the intersection) that is also named after the fellow and one of the more crowded markets in the metropolis. There are many jeepney lines with Blumentritt as part of their routes.

Approach to Blumentritt Station – the station is named after Ferdinand Blumentritt, an Austrian who was a close friend of the national hero Jose Rizal. The street leads to a large public market close to the station (near the intersection) that is also named after the fellow and one of the more crowded markets in the metropolis. There are many jeepney lines with Blumentritt as part of their routes.

Birds and other creatures being sold as pets around Blumentritt – many have been painted to attract children and other buyers curious at the colored birds.

Birds and other creatures being sold as pets around Blumentritt – many have been painted to attract children and other buyers curious at the colored birds.

Vendors line the Rizal Avenue, Blumentritt and the other side streets in the area, which is usually crowded no matter what day of the week it is.

Vendors line the Rizal Avenue, Blumentritt and the other side streets in the area, which is usually crowded no matter what day of the week it is.

Angry birds? A closer look reveals the birds as chicken chicks colored by the vendors to attract interest. Sadly, many of these do not survive to become full grown chickens and children (and adults) will be disappointed to discover later that the color comes off pretty quick when the chicks come in contact with water.

Angry birds? A closer look reveals the birds as chicken chicks colored by the vendors to attract interest. Sadly, many of these do not survive to become full grown chickens and children (and adults) will be disappointed to discover later that the color comes off pretty quick when the chicks come in contact with water.

There is a PNR Blumentritt Station and unless there’s been some radical clean-up of the area, this is pretty much what you’d see around the station – garbage, dirt, informal settlers and other characters. The building behind the station is a public school.

There is a PNR Blumentritt Station and unless there’s been some radical clean-up of the area, this is pretty much what you’d see around the station – garbage, dirt, informal settlers and other characters. The building behind the station is a public school.

The PNR Blumentritt Station has two platforms on either side of the double track. Security is quite lax and people, including children, cross the tracks freely. Fortunately, train service frequencies are quite low (about 1 per hour) so the risk of getting hit by a train is also low. The photo shows the view to the east of Rizal Avenue.

The PNR Blumentritt Station has two platforms on either side of the double track. Security is quite lax and people, including children, cross the tracks freely. Fortunately, train service frequencies are quite low (about 1 per hour) so the risk of getting hit by a train is also low. The photo shows the view to the east of Rizal Avenue.

On the left side of Rizal Avenue is a scene where people are oblivious to the railways with some even doing their cooking between the tracks.

On the left side of Rizal Avenue is a scene where people are oblivious to the railways with some even doing their cooking between the tracks.

Blumentritt Avenue is a very crowded street with a public school (building at right) just across the public market (at left). There are many vendors lined along the street and people as just about everywhere and without regard to vehicular traffic.

Blumentritt Avenue is a very crowded street with a public school (building at right) just across the public market (at left). There are many vendors lined along the street and people as just about everywhere and without regard to vehicular traffic.

Traffic congestion along Rizal Avenue is attributed mainly to the market and median barriers were constructed to reduce pedestrian crossings anywhere along the road. Commercial establishments line either side of Rizal Avenue, basically contributing to congestion in the area.

Traffic congestion along Rizal Avenue is attributed mainly to the market and median barriers were constructed to reduce pedestrian crossings anywhere along the road. Commercial establishments line either side of Rizal Avenue, basically contributing to congestion in the area.

Commercial establishments plus customers plus paratransit equal to traffic congestion

Commercial establishments plus customers plus paratransit equal to traffic congestion

16A busy side street in the Blumentritt area – there are no sidewalks so pedestrians and motor vehicles mix it up along the road.

16A busy side street in the Blumentritt area – there are no sidewalks so pedestrians and motor vehicles mix it up along the road.

Bulacan Street serves as an informal terminal for jeepneys. The road appears to be newly paved but there are no sidewalks and tents are found along the road often bearing the names of politicians sponsoring the tents for various purposes such as wakes and parties.

Bulacan Street serves as an informal terminal for jeepneys. The road appears to be newly paved but there are no sidewalks and tents are found along the road often bearing the names of politicians sponsoring the tents for various purposes such as wakes and parties.

Intersection with Pampanga Street, just before Rizal Avenue and the LRT line turns towards Aurora Boulevard and proceed to Caloocan City and Monumento.

Intersection with Pampanga Street, just before Rizal Avenue and the LRT line turns towards Aurora Boulevard and proceed to Caloocan City and Monumento.

More on Rizal Avenue in future post…

–

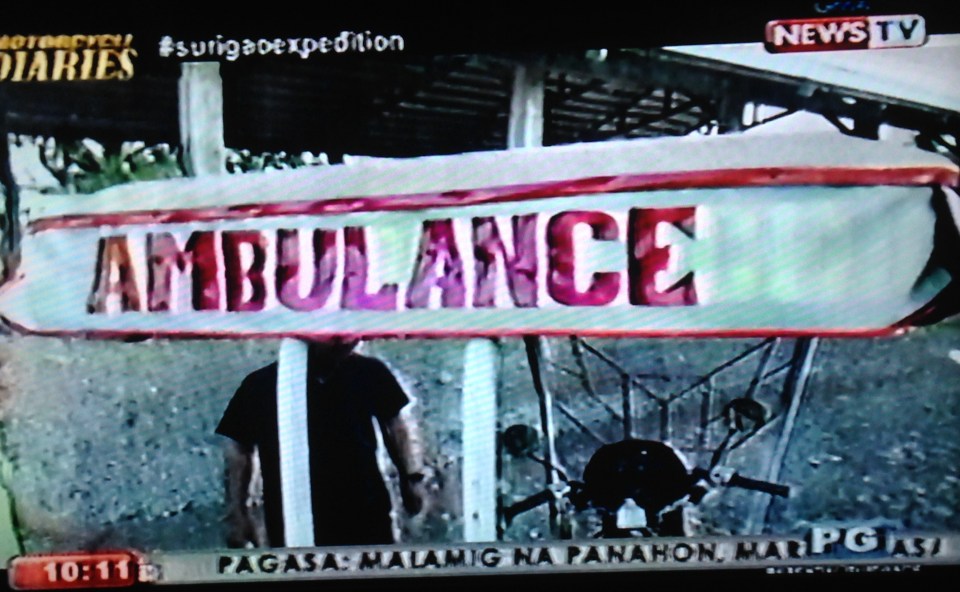

Unlike other habal-habal, this one has a roof and two planks on either side where patients lie down for transport. While I’ve seen habal-habals in Leyte and Samar that have roofs, the planks are more “skylab” than the typical habal-habal. “Skylab” is a term coined for the shape of motorcycle taxis with a plank installed perpendicular to its body. Passengers seated on the plank have to be balanced by the rider/driver.

Unlike other habal-habal, this one has a roof and two planks on either side where patients lie down for transport. While I’ve seen habal-habals in Leyte and Samar that have roofs, the planks are more “skylab” than the typical habal-habal. “Skylab” is a term coined for the shape of motorcycle taxis with a plank installed perpendicular to its body. Passengers seated on the plank have to be balanced by the rider/driver. All terrain – the habal-habal is popular in rural areas as it can operate on bad roads, trails, no roads and even cross rivers and streams.

All terrain – the habal-habal is popular in rural areas as it can operate on bad roads, trails, no roads and even cross rivers and streams. The documentary also had interviews with the owner and driver of the motorcycle ambulance.

The documentary also had interviews with the owner and driver of the motorcycle ambulance. Rough roads, typical of municipal and farm to market roads, do not deter haba-habal operations.

Rough roads, typical of municipal and farm to market roads, do not deter haba-habal operations. Rural roads are a big challenge given the conditions like these huge holes filled with water. I’ve seen roads like this that are like rivers or streams during the rainy season.

Rural roads are a big challenge given the conditions like these huge holes filled with water. I’ve seen roads like this that are like rivers or streams during the rainy season. Travel is quite treacherous along these roads and I can only imagine how difficult it would be to transport a patient on a motorcycle ambulance. The risks are quite high that there can be a mishap along the way that could result in not only serious injuries but death.

Travel is quite treacherous along these roads and I can only imagine how difficult it would be to transport a patient on a motorcycle ambulance. The risks are quite high that there can be a mishap along the way that could result in not only serious injuries but death. The sign makes it unmistakable for what the vehicle is for.

The sign makes it unmistakable for what the vehicle is for. The ride is a balancing act and the driver should be highly skilled for the task.

The ride is a balancing act and the driver should be highly skilled for the task. Patients or people needing medical attention are made to lie down on one of these cots on either side of the habal-habal. There are what looks like straps to secure the person. I assume that another person or weight should be placed on the other cot for balance. Likely, another person will ride behind the driver to care for the patient(s).

Patients or people needing medical attention are made to lie down on one of these cots on either side of the habal-habal. There are what looks like straps to secure the person. I assume that another person or weight should be placed on the other cot for balance. Likely, another person will ride behind the driver to care for the patient(s).