Home » Posts tagged 'policy' (Page 12)

Tag Archives: policy

Article on housing affordability and sprawl

There is a new article from Todd Litman that discusses the state of housing in the context of affordability and sprawl. While this is mainly based on the experiences in the US and Canada, there are many other cities from other countries involved. I noticed an interesting comment on his Facebook post about the elephant in the room being culture. I would tend to agree with this view and in the case of the Philippines is perhaps also heavily influenced by our being under a repressive Spanish regime that was succeeded by an American-style. I say repressive because although there was a semblance of planning during the Spanish period, the urban form revolved around the plaza where church, government, market and schools were located. Social class defined residential ‘development’ also followed this with the wealthier families having homes closer to the center while those in the lower income classes where farther and perhaps even beyond the reach of the sound of church bells. The Americans changed much of that and introduced a larger middle class and the incentive of becoming home and land owners, which during the Spanish period was practically non-existent except perhaps to the buena familias and ilustrados. Fast forward to the present, being a land owner is still very much a status symbol along with being a car owner. Homes in the urban centers (e.g., Makati CBD, Ortigas CBD, BGC, etc.) are very expensive and people would rather reside in the periphery (thus the sprawl) and do their long commutes.

Here is a link to the article:

Unaffordability is a Problem but Sprawl is a Terrible Solution

[Litman, T. (2017) Unaffordability is a problem but sprawl is a terrible solution, Planetizen, Retrieved from http://www.planetizen.com, February 17.]

What do you think?

–

Emergency powers to solve PH transport problems? – A long list of projects

I am sharing the long list of projects submitted by the Department of Transportation (DoTr) to the Senate Committee on Public Services chaired by Sen. Grace Poe. This is a public document and I think should be circulated for transparency and so people will know what projects are proposed to be covered

List of sectoral projects that the Department of Transportation intends to implement and draft bill for emergency powers: dotr-list-of-projects-and-draft-bill

I leave it up to my readers to determine which among the projects listed really require emergency powers. Many I think do not require emergency powers especially since the period requested for such powers is 2 years and not the duration of the current administration’s term. Perhaps those requiring emergency powers would be programs and projects aiming to overhaul our public transport system, which is currently much dependent on road-based modes. Public transportation services do not follow the suitable hierarchy as seen along major corridors served by low capacity modes. An overhaul (i.e., rationalisation) will touch the very sensitive nerves of bus, jeepney, UV express and tricycle operators and drivers and could trigger an avalanche of TROs to prevent or discourage government from doing what should have been done decades ago to bring order to our chaotic transport. I believe emergency powers coupled with the current admin’s political capital (and the “action man” image of Pres. Duterte) can help bring about genuine reform (and change!) to transport in our cities.

–

Emergence of motorcycle taxis in Metro Manila and other cities

Motorcycle taxis operate in many Asian cities. In Southeast Asia, in particular, there are formal and legal motorcycle taxi services in cities like Bangkok and Jakarta. These motorcycle taxis are called “habal-habal” in many parts of the Philippines and are accepted modes of public transport particularly in rural areas where roads are not the same quality as those in urban areas. Motorcycles and motor tricycles are the most preferred modes of transport and their characteristics are usually most suitable for such roads.

In Metro Manila, there are motorcycle taxis operating in many locations including Bonifacio Global City, Eastwood City and White Plains. These are basically discrete operations and providers are low key so as not to attract the attention of authorities. Services though are worst kept secrets considering they have a steady clientele. In Pasig City, and I assume other Metro Manila cities as well, there are ‘formal’ habal-habal terminals. I took a photo of one in a low income residential area that was designated as a relocation site for many informal settlers around the metropolis.

Habal-habal terminal in Pasig City near the Napindan Channel where the Pasig River meets Laguna de Bay

Habal-habal terminal in Pasig City near the Napindan Channel where the Pasig River meets Laguna de Bay

A friend at the Cebu City Traffic Operations Management (CCTO or CITOM) told us that there is a growing number of motorcycle riders offering transport services in their city. These are illegal but are being tolerated in many cases due to the growing demand for their services particularly during unholy hours late at night or in the early morning. I also saw many of these operating in Tacloban and even crossing the San Juanico Bridge to Samar Island from Leyte.

There are also many habal-habal in tourism areas including in island resorts where there is a lack of formal public transport services. This mode is a necessity and so far, there are only rare reports of these vehicles and their riders being involved in road crashes. This is the case despite their being perceived as unsafe modes of transport. I guess they will continue to be popular in rural areas and will quickly become popular should they be mainstreamed in urban areas just like their counterparts in neighboring countries in Southeast Asia. In fact, the demand is already there and just waiting to be tapped given the horrendous traffic jams that will drive people towards modes they think can allow them to escape traffic congestion.

–

Manila’s jeepney experiment

A few months ago, and almost right after the local elections, the City of Manila embarked on a campaign to reduce the number of colorum or illegal buses plying along the streets of the city. The result was confusion and mayhem as commuters and authorities were unprepared to deal with the sudden decrease in the number of buses (some companies even restrained all of their buses from entering Manila to protest the city’ move) and the jeepneys and UV express couldn’t handle the demand. Much of that seems to have been resolved and buses are now back in Manila; although whether all these buses are legal ones is still unclear. The city, it seems to some quarters, was only after buses with no formal terminals in the city and appeared to have made the drive to show bus companies who’s in-charge there.

Now comes a drive against jeepney drivers, particularly those undisciplined ones that are often found violating traffic rules and regulations, and endangering their passengers with their brand of driving. The result was a one-day strike (tigil pasada) of jeepneys belonging to the Federation of Jeepney Operators and Drivers Associations in the Philippines (FEJODAP), one of several organized jeepney groups in the country. Others like operators and drivers from Pasang Masda, PISTON and ACTO, opted not to join the transport strike. The result was a transport protest that had little impact on most people’s commutes though the group did manage to attract media attention and gave interviews to whoever cared to listen.

Not to judge Manila as I believe it has made huge strides by confronting the many urgent issues in transport in the city. Not many cities take these problems head on as Manila has done this year. However, the jury is still out there if their efforts have been effective and if these will be sustainable and not the ningas cogon kind that we have seen so much of in the past. For definitely, there are a lot of other transport issues that Manila needs to contend with including how to make the city more walkable and bicycle-friendly (not an easy task!) and how to address the excessive number of pedicabs (non-motorized 3-wheelers) and kuligligs (motorized 3-wheelers using generator sets or pumpboat motors for power) in the city. Hopefully, again, the city will be up to the task of addressing these problems along with the persistent congestion along its roads.

–

Tricycles in the Philippines – Part 1

We start the “ber” months strong with an initial feature on an ubiquitous mode of transport in the Philippines. While the jeepney seems to have had most of the attention when the subject of public transport in the Philippines is discussed, the truth is that there is arguably another, more dominant mode of public transport in the country. These are the tricycles, a motorized three-wheeler consisting of a motorcycle and a sidecar. You see these everywhere around the country in most cities and municipalities where they thrive particularly in residential areas. They are usually the only mode of public transport for most people in rural areas where local roads are typically narrow. In many cases the only roads connecting communities may be national roads. And so, there is really no other choice for tricycles but to travel along national roads and against existing laws prohibiting tricycles from these roads.

Tricycle along the motorcycle lane of Circumferential Road 5

Tricycle along the motorcycle lane of Circumferential Road 5

Tricycles racing along the Olongapo-Castillejos Road in Zambales

Tricycles racing along the Olongapo-Castillejos Road in Zambales

Tricycle along Romulo Highway, Tarlac

Tricycle along Romulo Highway, Tarlac

Tricycles along Catolico Avenue in Gen. Santos City

Tricycles along Catolico Avenue in Gen. Santos City

Unlike buses and jeepneys, tricycles are not regulated under the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB). Instead, they are under the local government units that through one office or another issue the equivalent of franchises for tricycles to operate legally. Fares are quite variable but are usually according to distance though there are special rates for when passengers want to have the vehicle for themselves much like a taxi.

Unfortunately, few LGUs have the capacity to determine the optimum number of tricycles for service areas under their jurisdictions. As tricycle operations are often the source of livelihood for many, the granting of franchises is often seen as a way for mayors to have influence over people who would have “utang na loob” (debt of gratitude) for being granted franchises. The tendency, therefore, is to have too many tricycles as mayors try to accommodate more applicants who seem to have no other options to earn income or to invest in. This poses a challenge to many who want to reform the system and modernize or upgrade public transport in cities around the country.

–

Manila’s bus experiment

Manila recently banned provincial and city buses from entering the city stating this is because many of them do not have franchises and/or terminals in the city. Those without franchises are the ones labeled as “colorum” or illegally operating public transport vehicles, which really don’t have a right to convey people in the first place. It’s become difficult to catch them because many carry well-made falsified documents. But it’s not really an issue if the LTFRB, LTO and LGUs would just cooperate to apprehend these colorum drivers. The LTFRB and LTO are under the DOTC, and so the agency is also responsible for policies and guidelines to be followed by the two under it. LGUs (and the MMDA in the case of MM) are tasked with traffic enforcement and so they can apprehend vehicles and act on traffic violations including operating without a franchise.

Those without terminals are both city and provincial buses. For city buses, this can be because they “turnaround” in Manila and operators do not feel the need to have a formal terminal. For example, G-Liner buses plying the Cainta-Quiapo route will stop at Quiapo only to unload Quiapo-bound passengers, and then switch signboards and proceed to load Cainta-bound passengers as they head back to Rizal. There is very little time spent as the bus makes the turnaround. It’s a different case for provincial buses, whose drivers should have the benefit of rest (same as their vehicles, which also need regularly maintenance checks) after driving long hours. Thus, if only for this reason they need to have formal, off-street terminals in the city. Following are photos I took near the Welcome Rotunda en route to a forum last Friday.

Commuters walking to cross the street at the Welcome Rotunda to transfer to jeepneys waiting for passengers to ferry to Manila.

Commuters walking to cross the street at the Welcome Rotunda to transfer to jeepneys waiting for passengers to ferry to Manila.

Commuters and cyclists moving along the carriageway as there are no pedestrian or cycling facilities in front of a construction site at the corner of Espana and Mayon Ave.

Commuters and cyclists moving along the carriageway as there are no pedestrian or cycling facilities in front of a construction site at the corner of Espana and Mayon Ave.

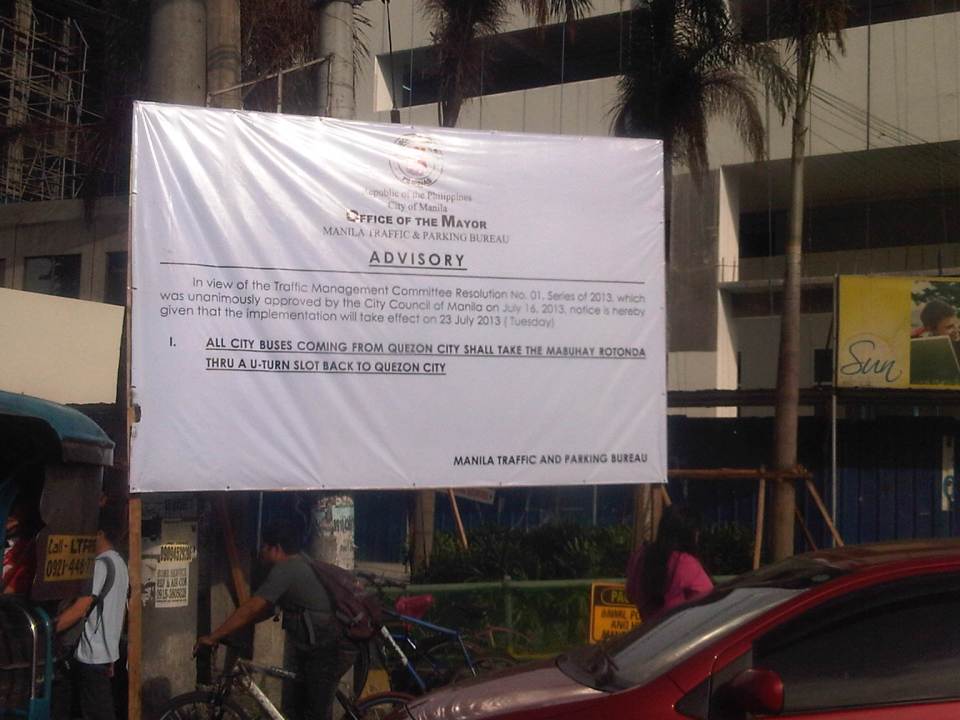

Advisory for buses coming from Quezon City

Advisory for buses coming from Quezon City

Commuters waiting for a jeepney ride along Espana just after the Welcome Rotunda

Commuters waiting for a jeepney ride along Espana just after the Welcome Rotunda

Some pedestrians opt to walk on instead of waiting for a ride. Manila used to be a walkable city but it is not one at present. Many streets have narrow sidewalks and many pedestrian facilities are obstructed by vendors and other obstacles.

Some pedestrians opt to walk on instead of waiting for a ride. Manila used to be a walkable city but it is not one at present. Many streets have narrow sidewalks and many pedestrian facilities are obstructed by vendors and other obstacles.

So, is it really a move towards better transport systems and services in Manila or is it just a publicity stunt? If it is to send a message to public transport (not just bus) operators and drivers that they should clean up their acts and improve the services including practicing safe driving, then I’m all for it and I believe Manila should be supported and lauded for its efforts. Unfortunately, it is unclear if this is really the objective behind the resolution. Also, whether it is a resolution or an ordinance, it is a fact that the move violates the franchises granted to the buses. These franchises define their routes and specify the streets to be plied by buses. Many LGUs in the past have executed their traffic schemes and other measures intended to address traffic congestion, without engaging the LTFRB or at least ask for the agency’s guidance in re-routing public transport. Of course, the LTFRB is also partly to blame as they have not been pro-active in reviewing and optimizing PT routes.

One opinion made by a former government transport official is that this is just a ploy by the city to force bus companies to establish formal terminals in the city. This will require operators to secure permits, purchase or lease land and build terminals. And so that means revenues for the city and perhaps more traffic problems in the vicinity of the terminals just like what’s happening in Quezon City (Cubao) and Pasay City (Tramo).

Transport planning is a big part of the DOTC’s mandate and both the LTO (in charge of vehicle registration and driver’s licenses) and LTFRB (in charge of franchising of buses, jeepneys and taxis) look to the agency for guidelines and policy statements they are to implement. Meanwhile, LGUs have jurisdiction over paratransit like tricycles and pedicabs. In the case of Manila, these paratransit also include the “kuligligs,” 3-wheeler pedicabs that were fitted with engines and have been allowed (franchised?) by the city to provide transport services in many streets. Unfortunately, most LGUs do not have capacity nor capability for transport planning and so are limited or handicapped in the way they deal with transport (and traffic) issues in their jurisdictions. We have always maintained and promoted the stand that the DOTC should extend assistance and expertise to LGUs and the LGUs should also actively seek DOTC’s guidance in matters pertaining to transport. There needs to be constant communication between the national and local entities with cooperation leading to better, more suitable policies being formulated and implemented at the local level.

–

Enforceable?

Whenever laws and regulations are crafted, one basic question that needs to be considered pertains to whether there is capacity to enforce such laws or regulations. This is quite logical and appeals to common sense since laws and regulations are practically prints on paper that will not have any impacts if not enforced properly and fairly. I mention “fairly” here because laws and regulation may also be the subject of abusive enforcement. That is, there have been cases where motorists are flagged down and charged with violations that are taken out of the context given the traffic conditions, and where the number of apprehensions are related to quotas set by authorities.

Take the case of the unwarranted or illegal use of sirens (wangwang) in the past. There were laws and regulations for its use but for a long time these laws and regulations were not enforced properly, leading to the wangwang’s abuse by many unscrupulous people. Almost everyone have practically given up on this abuse of the siren when a newly elected President expressed his dismay and ordered the eradication of illegal sirens. Almost overnight, “wangwangs” were confiscated by authorities inspired by the Commander-in-Chief’s orders or removed by owners themselves for fear of the law bearing down on them. This was enforcement at its best. Unfortunately, it was not replicated for other traffic laws and regulations, wasting valuable momentum and the opportunity to make things right along our streets and highways.

Quezon City’s Green Building Ordinance is quite good and well-meaning. It is very timely and relevant, and even includes provisions for upgrading transport in that city. Among others, it requires that tricycles be transformed into cleaner vehicles by stipulating the replacement of 2-stroke and even 4-stroke motorcycles with LPG or electric models. To date, nothing significant has been achieved to address issues pertaining to the tens of thousands of tricycles in Quezon City. The construction of green buildings in Quezon City cannot be mainly attributed to the ordinance but rather to owners and designers who are now much more aware of climate change and its impacts, and are progressive enough to design buildings that are environment-friendly. Of course, there are those who take to the “green” bandwagon but do nothing towards this end. Are these subject to evaluations and inspections that are the equivalent of enforcement?

Now comes a bicycle ordinance from Pasig City that is formally the “Bicycle Transportation Promotion Ordinance of 2011.” It is also good and well-meaning but the jury will definitely be out there if this initiative will be a successful and sustainable one. I am quite hopeful that it would be and not just end up as an example of coming up with laws because anything about the environment is in these days. The provision in the ordinance designating bicycle lanes and requiring establishments to provide bicycle racks for parking are all good but we have seen this before in an even bigger scale in the City of Marikina. There they constructed bikeways practically connecting all parts of the city and they were quite aggressive even after foreign support had ended. Politics and shortcomings (I wouldn’t say failure.) in encouraging people to cycle have made much of the on-street bicycle lanes practically taken over by motorized transport. Bicycle racks there are also being used by motorcycles and scooters. Pasig should learn from these experiences and it is hoped that the city succeed and become another example of EST to be replicated in other Philippine cities.

Traffic congestion in Metro Manila: Is the UVVRP still effective? – Part 2

In the past decade, there has been a sharp rise in the motorcycle ownership around the country and especially in Metro Manila. From about 1 million motorcycles registered in 2000, the number has increased to 3.2 million in 2009, a 320% increase over a period of 10 years. Motorcycles have become associated with mobility, in this case the motorized kind, and have become the mode of choice for many who choose to have their own vehicles but cannot afford a four-wheeler. These people also choose not to take public transport for a variety of reasons but mainly as they perceive their mobility to be limited should they use public transport services that are available to them. This rise of the motorcycle is also a response to the restrictions brought about by UVVRP with the scheme not covering motorcycles. In fact, should motorcycles be included in the UVVRP, it would be a nightmare for traffic enforcers to apprehend riders considering how they maneuver in traffic. Add to this the perception and attitude of riders that motorcycles are practically exempt from traffic rules and regulations (and traffic schemes!). One only needs to observe their behavior to validate the argument.

To understand UVVRP, it must also be assessed in the context of its original implementation when Metro Manila had to contend with congestion due to infrastructure projects being constructed everywhere during the 1990’s. EDSA MRT was being constructed, interchanges were also being put up, and a number of bridges were being widened to accommodate the increasing travel demand. Road widening projects generally benefit private vehicle users more than public transport users. In the case of Metro Manila, many areas are already built-up and acquisition of right of way for widening is quite difficult for existing roads. As such, it is very difficult to increase road capacities to accommodate the steady increase in the number of vehicles.

In transportation engineering, when traffic/transport systems management (TEM) techniques are no longer effective or yield marginal improvements we turn to travel demand management (TDM) schemes to alleviate congestion. In the former, we try to address congestion by tweaking the system (i.e., infrastructure) through road widening, adjustment of traffic signal settings, etc. while in the latter, we go to the root of the problem and try to manage the trips emanating from the trip generation characteristics of various land uses interacting with each other. By addressing the trip generation characteristics through restrictions, we influence travel demand and hopefully lessen traffic during the peak periods while distributing these to others.

This is the essence of UVVRP where the coding scheme targets particular groups of private cars (according to the end number on the license plate) each weekday. Meanwhile, the scheme is not implemented during weekends due to the perception that, perhaps, travel demand is less or more spread out during Saturdays and Sundays. However, there is a problem with this approach as the traffic taken away from the peak hours are transferred to other times of the day, thereby causing in some cases the extension of what was originally a peak hour unto a longer period. What was before a morning peak of say 7:30 – 8:30 AM becomes spread out into a peak period of 7:00 – 9:00 AM. The problem here is when you have major traffic generators like central business districts (e.g., Makati and Ortigas) where congestion is experience for more than 2 hours (e.g., 7:00 – 10:00 AM or 4:00 – 7:00 PM).

The UVVRP is not implemented in all of Metro Manila. Several LGUs, particularly those in the outer areas like Marikina City and Pateros. This is simply due to the information and observations of these cities that their roads are not affected by the build-up of traffic since most traffic is bound for the CBDs located in Makati, Pasig, Mandaluyong, Quezon City and Manila. This is the case also for LGUs in the periphery of Metro Manila like the towns in the province of Rizal, which is to the east of the metropolis, where the typical behavior of traffic is outbound in the morning and inbound in the afternoon. The great disparity between inbound and outbound traffic is evident in the traffic along Ortigas Avenue where authorities have even implemented a counterflow scheme to increase westbound road capacity.

There have also been observations of traffic easing up during the mid-day. As such, the MMDA introduced a window from 10:00 AM to 3:00 PM to allow all vehicles to travel during that period while retaining the restrictions of the number coding scheme from 7:00 – 10:00 AM and 3:00 – 7:00 PM. However, while many LGUs applied the window, some and particularly those found in central part of the Metropolis like Makati, retained the 7:00 AM – 7:00 PM ban. This stems from their perspective that traffic does not ease up at all (e.g., try driving along Gil Puyat Ave. during lunchtime) along their streets during the window period.

Nowadays, there seems to be the general perception that one can no longer distinguish between traffic during the coding period and the window. Traffic congestion is everywhere and there are few opportunities for road widening. Traffic signal control adjustments are limited to those intersections where signals have been retained (mostly in Makati) since the MMDA replaced signalized intersections with U-turn slots during a past administration where the U-turn was hailed as the solution to the traffic mess.

Traffic congestion in Metro Manila: Is the UVVRP still effective? – Part 1

I was interviewed last week about the traffic congestion generally experienced along major roads in Metro Manila. I was asked whether I thought the Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program (UVVRP) more popularly known as the number coding scheme was still effective, and I replied that based on what we are experiencing it is obviously not effective anymore. The reasoning here can be traced from the fact that when the scheme was first formulated and implemented, the main assumption was that if the number of license plates on registered vehicles were equally distributed among the 10 digits (1 to 0), then by restricting 2 digits indicated as the end/last number on a plate we could automatically have a 20% reduction in the number vehicles. This rather simplistic assumption was sound at the time but apparently did not take into consideration that eventually, people owning vehicles will be able to adjust to the scheme one way or another.

One way to adjust when the number coding scheme was implemented was to change traveling times. Everyone knew that the scheme was enforced from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM (i.e., there was no 10:00 AM to 3:00 PM window at the time) and so people only had to travel from the origins to their destinations before 7:00 AM. Similarly, they would travel back after 7:00 PM, which partly explains why after 7:00 PM there is usually traffic congestion due to “coding” vehicles coming out to travel. In effect, the “coding” vehicle is not absent from the streets that day. Instead, it is only used during the time outside of the “coding” or restricted period.

Another way that was actually a desired impact of the coding scheme was for people to shift to public transport, at least for the day when their vehicle was “coding.” That way, the vehicle is left at home and there is one less vehicle for every person who opted to take public transport. This, however, was not to be and people did not shift to public transport. Perhaps the quality of services available or provided to them were just not acceptable to most people and so they didn’t take public transport and a significant number instead opted for a third way.

That third way to adjust was one that was the least desirable of the consequences of number coding – people who could afford it bought another vehicle. This was actually a result that could have been expected or foreseen given the trends and direct relationship between increases in income associated with economic growth where people would eventually be able to afford to buy a vehicle. Actually, there is no problem with owning a car. The concern is when one uses it and when he opts to travel. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that people started buying new cars outright, making this something like an overnight phenomenon. It happened over several years and involved a cycle that starts when the wealthier people decide to purchase a new vehicle and discards their old ones. These used vehicles become available on the “second hand” market and are purchased by those with smaller budgets. Some of these may have even older vehicles that they will in turn discard, and eventually be owned by other people with even less budget. Note that in this cycle, very few vehicles are actually retired, if at all considering this country has no retirement policy for old vehicles. The end result? More cars on the roads and consequently, more severe and more frequent congestion.

Below is an excerpt from the news report on News TV Channel 11:

Upgrades: the Ayala BRT

The Ayala Land Inc. (ALI) has been issuing press releases about their plan to put up a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system for the Makati CBD and the Bonifacio Global City. The system will serve both the old financial center in Makati and the rapidly emerging one in Taguig, connecting the two via Ayala Avenue-McKinley Road and Gil Puyat (Buendia) Avenue-Kalayaan Avenue corridors. It is a project that is long overdue although the buses serving the Fort have shown us at least what a higher capacity mode of transport can do if managed properly.

The Fort Buses load and unload passengers at designated stops. They follow traffic rules and regulations enforced more strictly inside the Global City. Many of the newer bus units also happen to have layouts that are more appropriate for city operations. The Mercedes Benz coaches are designed such that they can accommodate more passengers as they have ample standing space and there are only enough seats for passengers who may actually need them like the elderly, pregnant women, persons with disabilities, and perhaps those who are burdened with heavy bags or packages. The doors of these units are also designed for more efficient fare collection and discharging of passengers, with the narrower front door accommodating boarding commuters who are already queued at bus stops and the wide two door rear egress allowing for efficient alighting. Surely, an automated fare collection system such as those using smart cards or other machines will be in place in the near future and greatly improve the operations of these buses. But the most significant feature, it seems, of the Fort Bus is the compensation scheme for its employees, particularly its drivers. Unlike most bus companies, Fort Bus drivers are given a regular monthly salary and reportedly enjoy benefits much like regular employees in typical companies or offices. This feature, I believe, is what makes it work in the first place and what is required for a transformation in public transport services as it does away with the rabid competition that is the derivative of a commission-based or “boundary” system compensation scheme that is used for both buses and jeepneys.

Considering the calls for more efficient as well as more safer public transport systems, let this Ayala BRT be a test case for what to do with transport systems that should have been phased out a long time ago (jeepneys) along corridors or routes that demand higher capacity vehicles. Public utility vehicles with low capacities and perhaps low quality of service should be replaced by more efficient modes especially along arterials. Also, all the elements are there for a potentially successful PPP in transport. You have a major player from the private sector (Ayala) offering to put up a system that it has studied and designed over the past few years. You have two CBDs in Makati and Taguig that currently serve as the present and future financial centers. And you have the challenge of doing away with an inefficient transport system. Though there sure will be compromises that are not necessarily palatable (e.g., re-routing PUJ and PUB lines) the government should start realizing that it should be more deliberate and even unforgiving when it deals with the issue on PUJ and PUB franchises here.

The local governments of Makati and Taguig should cooperate with Ayala to make this work for these LGUS should put aside certain interests including those pertaining to PUJ and PUB operators and drivers, many of whom may be their constituents and comprise a significant part of their voting populations. The LGUs should facilitate discussions including those dealing with livelihood and othe social issues that are the province of local governments. The Land Transport Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) should get out of its shell and make a stand now considering the opportunity for public transport transformation. And its mother agency, the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) should support this stand, all out, if only to show that it is indeed committed to reforming and modernizing public transport systems in this country.

A BRT finally being realized for Makati and Global City will indeed be a showcase. We just hope that it will be a showcase of an efficient transformation of a public transport system from an outdated to a modern and efficient one rather than a showcase of futility and ineptness on the side of those in government. As they say, something has to start somewhere. A modern, efficient public transport system that is deserved by Filipinos may just start in Makati and Taguig, and with a BRT that may actually mean “better rapid transit.”