Home » Posts tagged 'traffic schemes' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: traffic schemes

Traffic consultants for Philippine cities?

I was driving to the office one morning, and as I was slowing down to stop at the Masinag junction I spotted a familiar face giving instructions to Antipolo traffic personnel. Robert Nacianceno was formerly the General Manager (Undersecretary level position) with the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) when it was chaired by Bayani Fernando, the first MMDA Chair to gain a cabinet level post (previously the MMDA Chair was not a Secretary level position). He was in an office barong while leading Antipolo staff in positioning orange traffic cones to mark the lanes for turning traffic along the Sumulong Highway approach from Antipolo.

Nacianceno is a cyclist so I would like to think that he can take that perspective in transport planning and traffic management for Antipolo. Unfortunately, his track record at the MMDA does not provide strong evidence as to his competence in transport planning or traffic management. Insiders say most policies and schemes during BF’s time was the latter’s ideas (e.g., U-turns, bike lanes, etc.) and he had his own consultant (and reportedly an inner circle) for various matters including traffic. In fairness to the man, Nacianceno probably has tremendous experience on the job but one has to note that there were other people with the MMDA who also dabbled in transport and traffic. Also, as GM he had other things to attend to during his stint including waste management and flood control.

Remember this guy? He used to be the MMDA GM during BF’s stint at the agency.

Remember this guy? He used to be the MMDA GM during BF’s stint at the agency.

I recall that the previous traffic consultant of Antipolo City was also a former MMDA official, Ernesto Camarillo. Unfortunately, I couldn’t say that Antipolo traffic improved during the last few years. Based on what I have seen in my daily commute, transport and traffic conditions have degenerated. Antipolo is overrun by tricycles and people generally do not follow rules and regulations. Informal terminals dot the city and you don’t have to go far to find inappropriate terminals as these are in plain view and across from the Rizal Provincial Capitol. Antipolo has a new mayor in the former Rizal Governor and his mother now sits as governor of the province. I’m crossing my fingers as to how they will improve transport and traffic in Antipolo if there is really a desire to do so. For starters, is there a transport and traffic plan for this Highly Urbanized City (HUC)? There should be one as the city needs it badly together with a land use plan to bring some order in development.

Antipolo is rapidly developing but at the same time conditions (including traffic) are also rapidly deteriorating. Hopefully, the LGU will address these issues and eventually make this city a modern one and fit for its being an HUC as well as a popular pilgrimage site for decades if not centuries due to the Shrine of Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage (Is there some irony here?). Nacianceno’s work has just started and I hope he is up to the challenge of bringing order to Antipolo’s chaotic transport and traffic situation. I hope, too, that he will take note of good practices in other cities (Philippine or foreign) and won’t be relying purely on his experiences in Metro Manila. And hopefully, whatever improvements from the traffic schemes he will be introducing and implementing will be felt immediately by travellers. Good luck!

–

Manila’s bus experiment

Manila recently banned provincial and city buses from entering the city stating this is because many of them do not have franchises and/or terminals in the city. Those without franchises are the ones labeled as “colorum” or illegally operating public transport vehicles, which really don’t have a right to convey people in the first place. It’s become difficult to catch them because many carry well-made falsified documents. But it’s not really an issue if the LTFRB, LTO and LGUs would just cooperate to apprehend these colorum drivers. The LTFRB and LTO are under the DOTC, and so the agency is also responsible for policies and guidelines to be followed by the two under it. LGUs (and the MMDA in the case of MM) are tasked with traffic enforcement and so they can apprehend vehicles and act on traffic violations including operating without a franchise.

Those without terminals are both city and provincial buses. For city buses, this can be because they “turnaround” in Manila and operators do not feel the need to have a formal terminal. For example, G-Liner buses plying the Cainta-Quiapo route will stop at Quiapo only to unload Quiapo-bound passengers, and then switch signboards and proceed to load Cainta-bound passengers as they head back to Rizal. There is very little time spent as the bus makes the turnaround. It’s a different case for provincial buses, whose drivers should have the benefit of rest (same as their vehicles, which also need regularly maintenance checks) after driving long hours. Thus, if only for this reason they need to have formal, off-street terminals in the city. Following are photos I took near the Welcome Rotunda en route to a forum last Friday.

Commuters walking to cross the street at the Welcome Rotunda to transfer to jeepneys waiting for passengers to ferry to Manila.

Commuters walking to cross the street at the Welcome Rotunda to transfer to jeepneys waiting for passengers to ferry to Manila.

Commuters and cyclists moving along the carriageway as there are no pedestrian or cycling facilities in front of a construction site at the corner of Espana and Mayon Ave.

Commuters and cyclists moving along the carriageway as there are no pedestrian or cycling facilities in front of a construction site at the corner of Espana and Mayon Ave.

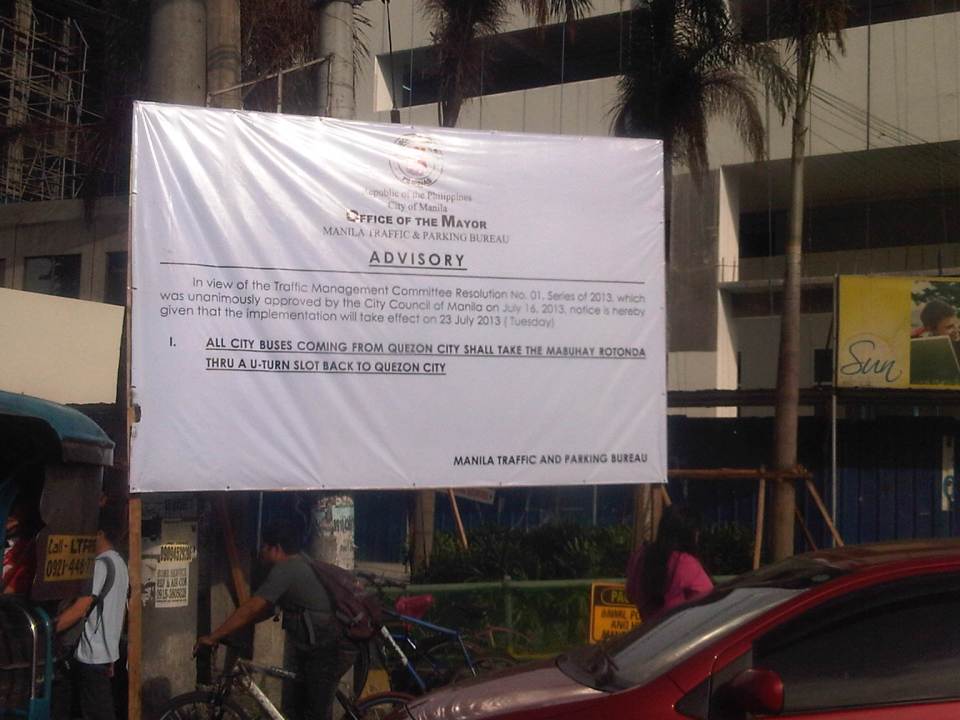

Advisory for buses coming from Quezon City

Advisory for buses coming from Quezon City

Commuters waiting for a jeepney ride along Espana just after the Welcome Rotunda

Commuters waiting for a jeepney ride along Espana just after the Welcome Rotunda

Some pedestrians opt to walk on instead of waiting for a ride. Manila used to be a walkable city but it is not one at present. Many streets have narrow sidewalks and many pedestrian facilities are obstructed by vendors and other obstacles.

Some pedestrians opt to walk on instead of waiting for a ride. Manila used to be a walkable city but it is not one at present. Many streets have narrow sidewalks and many pedestrian facilities are obstructed by vendors and other obstacles.

So, is it really a move towards better transport systems and services in Manila or is it just a publicity stunt? If it is to send a message to public transport (not just bus) operators and drivers that they should clean up their acts and improve the services including practicing safe driving, then I’m all for it and I believe Manila should be supported and lauded for its efforts. Unfortunately, it is unclear if this is really the objective behind the resolution. Also, whether it is a resolution or an ordinance, it is a fact that the move violates the franchises granted to the buses. These franchises define their routes and specify the streets to be plied by buses. Many LGUs in the past have executed their traffic schemes and other measures intended to address traffic congestion, without engaging the LTFRB or at least ask for the agency’s guidance in re-routing public transport. Of course, the LTFRB is also partly to blame as they have not been pro-active in reviewing and optimizing PT routes.

One opinion made by a former government transport official is that this is just a ploy by the city to force bus companies to establish formal terminals in the city. This will require operators to secure permits, purchase or lease land and build terminals. And so that means revenues for the city and perhaps more traffic problems in the vicinity of the terminals just like what’s happening in Quezon City (Cubao) and Pasay City (Tramo).

Transport planning is a big part of the DOTC’s mandate and both the LTO (in charge of vehicle registration and driver’s licenses) and LTFRB (in charge of franchising of buses, jeepneys and taxis) look to the agency for guidelines and policy statements they are to implement. Meanwhile, LGUs have jurisdiction over paratransit like tricycles and pedicabs. In the case of Manila, these paratransit also include the “kuligligs,” 3-wheeler pedicabs that were fitted with engines and have been allowed (franchised?) by the city to provide transport services in many streets. Unfortunately, most LGUs do not have capacity nor capability for transport planning and so are limited or handicapped in the way they deal with transport (and traffic) issues in their jurisdictions. We have always maintained and promoted the stand that the DOTC should extend assistance and expertise to LGUs and the LGUs should also actively seek DOTC’s guidance in matters pertaining to transport. There needs to be constant communication between the national and local entities with cooperation leading to better, more suitable policies being formulated and implemented at the local level.

–

Traffic Congestion in Metro Manila: Is the UVVRP Still Effective? -Conclusion

The MMDA always reports what it claims as improvements of travel speeds along EDSA that past years. They have pointed to this as evidence that traffic congestion is being addressed and that programs like the UVVRP are effective in curbing congestion. However, many traffic experts have cautioned against making sweeping generalizations pertaining to the effectiveness of schemes especially if the evidence put forward is limited and where data seems to have been collected under undesirable (read: unscientific) circumstances.

The MMDA also has been using and to some extent overextending its use of a micro-simulation software that is employs to demonstrate the potential effectiveness of its proposed traffic schemes. The software has an excellent animation feature that can make the untrained eye believe in what is being shown as The problem here is when one realizes that computer software will only show what the programmer/operator wants, and is perhaps an example where the term “garbage in, garbage out” is very much applicable. And this is especially true should the computer model be uncalibrated and unvalidated according to guidelines that are well established, and extensively discussed and deliberated in a wealth of academic references. The fallacy of employing advanced tools to demonstrate how one’s proposal is better than another was highlighted when the DPWH acquired the same tool and came up with an entirely different result for an analysis being made for the same project by that agency and the MMDA. Surely this resulted in confusion as the outcomes of the simulation efforts of both agencies practically negated each other.

It should be pointed out that such micro-simulation software is unsuitable for the task of determining whether metro-wide schemes such as the UVVRP is still effective given the actions of those affected by the scheme. What is required is a macroscopic model that would take into account the travel characteristics of populations in Metro Manila and its surrounding areas (cities and towns in the provinces of Rizal, Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna). There are quite a few of these models available but most if not all were derived from the one developed under the Metro Manila Urban Transport Integration Study (MMUTIS) that was completed in 1999. The main beneficiary from the outcomes of MMUTIS happens to be the MMDA but for some reason, that agency failed to build capacity for maintaining and updating/upgrading the model. As such, the agency missed a great opportunity to invest in something that they could have used to develop and evaluate traffic schemes to address congestion and other traffic issues in Metro Manila, as well as to assess the impacts of new developments.

Metro Manila has come to a point where its options for alleviating congestion are becoming more and more limited. The combination of a still increasing rate of motorization and private vehicle use have definitely contributed to congestion while there are also perceptions of a decline in public transport use in the metropolis. The share of public transport users in most Philippine cities and municipalities range from 80 – 90 %, while in many highly urbanized cities the tendency seems to be a decline for this share as more people are choosing to purchase motorcycles to enhance their mobility and as a substitute to cars. This trend towards motorcycle use cannot be denied based on the steep increase in ownership and the sheer number of motorcycles we observe in traffic everyday.

Metro Manila needs to retain the substantial public transport share while accepting that motorcycle ownership will continue to chip off commuters. The latter phenomenon can be slowed down should authorities strictly enforce traffic rules and regulations on motorcyclists, effectively erasing the notion that the latter group is “exempted” from such. The bigger and more urgent issue is how to put up long overdue mass transport infrastructure that is direly needed in order to create another opportunity for rationalization transport services. We seem to like that word “rationalization” without really understanding and acting on what is required to once and for all address transport problems in the metropolis. We are not lacking for examples of good practices that are both effective and sustainable including those in the capital cities of our ASEAN neighbors. However, we seem to be unable to deliver on the infrastructure part that we have tended to over-rely on a TDM scheme that has long lost much of its effectiveness. The evidence is quite strong for this conclusion and perhaps we should stop being in denial in as far as the UVVRP’s effectiveness is concerned. Efforts should be turned towards building the necessary infrastructure and making public transport attractive so that private car and motorcycle users will be left with no excuse to shift to public transport use. It is inevitable that at some time they will understand the cost of congestion and that they will have to pay for their part in congestion like what is being done along tollways or, in the more sophisticated and mature example, Singapore. But this cannot be realized if we continue to fail in putting up the infrastructure Metro Manila so direly requires.

Traffic congestion in Metro Manila: Is the UVVRP still effective? – Part 2

In the past decade, there has been a sharp rise in the motorcycle ownership around the country and especially in Metro Manila. From about 1 million motorcycles registered in 2000, the number has increased to 3.2 million in 2009, a 320% increase over a period of 10 years. Motorcycles have become associated with mobility, in this case the motorized kind, and have become the mode of choice for many who choose to have their own vehicles but cannot afford a four-wheeler. These people also choose not to take public transport for a variety of reasons but mainly as they perceive their mobility to be limited should they use public transport services that are available to them. This rise of the motorcycle is also a response to the restrictions brought about by UVVRP with the scheme not covering motorcycles. In fact, should motorcycles be included in the UVVRP, it would be a nightmare for traffic enforcers to apprehend riders considering how they maneuver in traffic. Add to this the perception and attitude of riders that motorcycles are practically exempt from traffic rules and regulations (and traffic schemes!). One only needs to observe their behavior to validate the argument.

To understand UVVRP, it must also be assessed in the context of its original implementation when Metro Manila had to contend with congestion due to infrastructure projects being constructed everywhere during the 1990’s. EDSA MRT was being constructed, interchanges were also being put up, and a number of bridges were being widened to accommodate the increasing travel demand. Road widening projects generally benefit private vehicle users more than public transport users. In the case of Metro Manila, many areas are already built-up and acquisition of right of way for widening is quite difficult for existing roads. As such, it is very difficult to increase road capacities to accommodate the steady increase in the number of vehicles.

In transportation engineering, when traffic/transport systems management (TEM) techniques are no longer effective or yield marginal improvements we turn to travel demand management (TDM) schemes to alleviate congestion. In the former, we try to address congestion by tweaking the system (i.e., infrastructure) through road widening, adjustment of traffic signal settings, etc. while in the latter, we go to the root of the problem and try to manage the trips emanating from the trip generation characteristics of various land uses interacting with each other. By addressing the trip generation characteristics through restrictions, we influence travel demand and hopefully lessen traffic during the peak periods while distributing these to others.

This is the essence of UVVRP where the coding scheme targets particular groups of private cars (according to the end number on the license plate) each weekday. Meanwhile, the scheme is not implemented during weekends due to the perception that, perhaps, travel demand is less or more spread out during Saturdays and Sundays. However, there is a problem with this approach as the traffic taken away from the peak hours are transferred to other times of the day, thereby causing in some cases the extension of what was originally a peak hour unto a longer period. What was before a morning peak of say 7:30 – 8:30 AM becomes spread out into a peak period of 7:00 – 9:00 AM. The problem here is when you have major traffic generators like central business districts (e.g., Makati and Ortigas) where congestion is experience for more than 2 hours (e.g., 7:00 – 10:00 AM or 4:00 – 7:00 PM).

The UVVRP is not implemented in all of Metro Manila. Several LGUs, particularly those in the outer areas like Marikina City and Pateros. This is simply due to the information and observations of these cities that their roads are not affected by the build-up of traffic since most traffic is bound for the CBDs located in Makati, Pasig, Mandaluyong, Quezon City and Manila. This is the case also for LGUs in the periphery of Metro Manila like the towns in the province of Rizal, which is to the east of the metropolis, where the typical behavior of traffic is outbound in the morning and inbound in the afternoon. The great disparity between inbound and outbound traffic is evident in the traffic along Ortigas Avenue where authorities have even implemented a counterflow scheme to increase westbound road capacity.

There have also been observations of traffic easing up during the mid-day. As such, the MMDA introduced a window from 10:00 AM to 3:00 PM to allow all vehicles to travel during that period while retaining the restrictions of the number coding scheme from 7:00 – 10:00 AM and 3:00 – 7:00 PM. However, while many LGUs applied the window, some and particularly those found in central part of the Metropolis like Makati, retained the 7:00 AM – 7:00 PM ban. This stems from their perspective that traffic does not ease up at all (e.g., try driving along Gil Puyat Ave. during lunchtime) along their streets during the window period.

Nowadays, there seems to be the general perception that one can no longer distinguish between traffic during the coding period and the window. Traffic congestion is everywhere and there are few opportunities for road widening. Traffic signal control adjustments are limited to those intersections where signals have been retained (mostly in Makati) since the MMDA replaced signalized intersections with U-turn slots during a past administration where the U-turn was hailed as the solution to the traffic mess.

Traffic congestion in Metro Manila: Is the UVVRP still effective? – Part 1

I was interviewed last week about the traffic congestion generally experienced along major roads in Metro Manila. I was asked whether I thought the Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program (UVVRP) more popularly known as the number coding scheme was still effective, and I replied that based on what we are experiencing it is obviously not effective anymore. The reasoning here can be traced from the fact that when the scheme was first formulated and implemented, the main assumption was that if the number of license plates on registered vehicles were equally distributed among the 10 digits (1 to 0), then by restricting 2 digits indicated as the end/last number on a plate we could automatically have a 20% reduction in the number vehicles. This rather simplistic assumption was sound at the time but apparently did not take into consideration that eventually, people owning vehicles will be able to adjust to the scheme one way or another.

One way to adjust when the number coding scheme was implemented was to change traveling times. Everyone knew that the scheme was enforced from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM (i.e., there was no 10:00 AM to 3:00 PM window at the time) and so people only had to travel from the origins to their destinations before 7:00 AM. Similarly, they would travel back after 7:00 PM, which partly explains why after 7:00 PM there is usually traffic congestion due to “coding” vehicles coming out to travel. In effect, the “coding” vehicle is not absent from the streets that day. Instead, it is only used during the time outside of the “coding” or restricted period.

Another way that was actually a desired impact of the coding scheme was for people to shift to public transport, at least for the day when their vehicle was “coding.” That way, the vehicle is left at home and there is one less vehicle for every person who opted to take public transport. This, however, was not to be and people did not shift to public transport. Perhaps the quality of services available or provided to them were just not acceptable to most people and so they didn’t take public transport and a significant number instead opted for a third way.

That third way to adjust was one that was the least desirable of the consequences of number coding – people who could afford it bought another vehicle. This was actually a result that could have been expected or foreseen given the trends and direct relationship between increases in income associated with economic growth where people would eventually be able to afford to buy a vehicle. Actually, there is no problem with owning a car. The concern is when one uses it and when he opts to travel. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that people started buying new cars outright, making this something like an overnight phenomenon. It happened over several years and involved a cycle that starts when the wealthier people decide to purchase a new vehicle and discards their old ones. These used vehicles become available on the “second hand” market and are purchased by those with smaller budgets. Some of these may have even older vehicles that they will in turn discard, and eventually be owned by other people with even less budget. Note that in this cycle, very few vehicles are actually retired, if at all considering this country has no retirement policy for old vehicles. The end result? More cars on the roads and consequently, more severe and more frequent congestion.

Below is an excerpt from the news report on News TV Channel 11:

Ortigas traffic

Ortigas Avenue traffic is very familiar to me. For one, I have used the road since childhood because it was the most direct route to and from school. We lived in Cainta and I went to school for 11 years in Mandaluyong. Before that, I even have memories of the section of Ortigas Avenue where Valle Verde phases are now located being carved quite literally from the adobe mountain that it was back in the mid 1970’s. Ortigas was the only access for those living in the east, particularly the Antipolo-Cainta-Taytay-Binangonan-Angono towsn of Rizal Province, for quite some time. Marcos Highway was still a dirt road and Marikina and Cogeo were somewhat out of the way. Meanwhile, Ortigas was already an important corridor as it led to Antipolo, an important religious and popular recreational site.

As the populations of the Rizal towns I mentioned increased, mostly due to their proximity to Metro Manila and being popular for residential developments then as now, Ortigas became congested. The avenue itself was widened but as any traffic engineering textbook will tell us, the bottlenecks were really the bridges. And I also remember the Rosario Bridge across the Pasig River being widened twice, both before the Manggahan Floodway was constructed. I experienced the impacts of both widening endeavors and did not enjoy having to wake up earlier than when I usually did because of the horrific traffic. It was worse, I guess, when the Manggahan Floodway was being constructed and there were too few options as to alternative routes. In fact, there were too few bridges across the floodway and Pasig River.

Nowadays, traffic congestion along Ortigas Avenue seem much worse than before. This I get from my siblings who still use the corridor as part of their routes to their workplaces. I trust in their assessment considering that my brother went to the same Mandaluyong school I attended and my sister attended another exclusive school in Pasig. My sister’s husband attests to the worsening traffic as he’s also lived at a residential area along Ortigas. From firsthand observation, I can also validate that Ortigas is worse these days than say 10 and 20 years ago.

The counterflow scheme along Ortigas is not new. In fact, my father and our school service drivers knew about this and would often time their trips to coincide with the scheme so that they can drive almost continuously to their destinations in the morning. Back then, I remember that the counterflow scheme was in effect for 10 to 15 minutes at the 0630, 0700, 0730 and 0800 times. It was also actually a regulated one-way scheme and was called thus since it benefited vehicles traveling along the outbound (from Rizal) direction. Inbound traffic were stopped at strategic points along the avenue including Rosario Bridge.

Such schemes are possible only when there is a dominant direction during the peak hours. In the case of Ortigas the directional distribution before was practically 90% outbound in the morning peak. A one-way, counterflow scheme was possible and practical for an undivided road. There were no medians or island to prevent vehicles from moving over to the opposing lane and back. That was then and at a time when I suppose that there were less friction along the avenue. Road friction, particularly those caused by public utility vehicles stopping for passengers, is more serious these days as the number of PUVs have also dramatically increased to address the demand for travel. Only now, there seem to be more informal terminals and longer dwell times at strategic points along Ortigas. These cause the bottlenecks that are also complicated by Ortigas now having median barriers along its length.

I believe congestion can be significantly alleviated by developing and implementing a simple dispatching system for PUVs along strategic points like the designated loading and unloading zones at either ends of the Manggahan and Rosario bridges. The dispatching system should be implemented along with a strict enforcement regime to ensure quick boarding and alighting times and prohibiting PUVs from spilling over and occupying other lanes, that often results in blockage of general traffic. Perhaps, a counter-flow scheme may be re-evaluated and become unnecessary. This recommendation comes in the heels of a survey we conducted along Ortigas only yesterday, February 10 in Manila, where I personally experienced PUVs making a terminal out of the outbound lanes before the Manggahan bridge and effectively blocking outbound traffic along the avenue. I can imagine the frustration of those caught in traffic along Ortigas and its implications along the extension and the Imelda and Bonifacio Avenues from Cainta Junction. The result of that blockage and the implementation of a counterflow around 0715 is shown in the following two photos I took.

Figure A: Image downstream along Ortigas Avenue (to Rosario Bridge and C5)

Figure A: Image downstream along Ortigas Avenue (to Rosario Bridge and C5)

Figure B: Image upstream along Ortigas Avenue (from Cainta Junction)

Figure B: Image upstream along Ortigas Avenue (from Cainta Junction)

It is clear from the photos that private vehicles were the ones who benefited from the counterflow. However, it is interesting to see that the outbound lanes were practically empty especially along the Manggahan Bridge. This clearly shows that there is actually enough road capacity but that it is not utilized (and counterflows were required) because of the blockage caused by PUVs upstream of our position. This is another strong case for going back to the basics in as far as traffic engineering and management is concerned. It does not take a PhD degree to see what’s wrong in the photos and certainly an advanced degree is not required for a solution to the problem.

Ningas Cogon

After focusing on one negative trait, I didn’t expect to be writing immediately about another. Again, I do this in the context of transport and traffic, and to drive home the point that we really need to go back to the basics in as far as solving transport and traffic problems in this country is concerned. Ningas cogon refers to how a type of grass burns when set on fire. There is initially an intense burning of the grass but after a short time it dies out. This behavior of the burning is often alluded to when describing efforts that are not sustained and especially those that showed enthusiasm (and therefore promise) only at the start. It is also associated with an initial show of interest that eventually and shortly wanes for one reason or another.

Only two weeks back I was writing about Commonwealth Avenue and how it was called a killer highway. At the time, I was hopeful that the renewed effort to impose discipline among motorists and especially public utility vehicle drivers and pedestrians would result in a significant improvement of safety along the highway. The initial results seemed to be encouraging, with a dramatic decrease in the number of road crashes and deaths in the first few days. I even had several opportunities to observe the efforts of enforcers, the combination of MMDA, PNP and QC personnel, to keep PUVs along their designated lanes and remind motorists and pedestrians to follow rules and regulations. I was pleasantly surprised, for example, to see vehicles “slow down” to 60 kph instead of the expressway speeds they usually attain along Commonwealth. At the Philcoa area near Commonwealth’s junction with the Elliptical Road, PUVs were being guided through the loading and unloading area and violators were quickly apprehended by MMDA and PNP personnel closely watching the traffic.

Meanwhile, I read a few newspaper columns giving mixed reviews about the program. One column in particular from a major daily mentioned that the effort lasted only a few days and that traffic reverted back to pre-discipline zone times. My reaction was one of disappointment, not for the government but for the columnist whom I thought came up with a premature conclusion, given that changing motorist and pedestrian behavior and attitudes along a major thoroughfare would take time. I did mention though in my previous post that enforcement should be firm and sustained in order for it to be successful and enduring. Also, I was already wary of the tendency for such programs to go the way of others before it – ningas cogon.

Last Sunday, I drove along Commonwealth on my way to visit my in-laws in Novaliches. I decided to do an experiment using a simple method that I learned when I was a student at University and which I also teach my students in undergrad civil engineering. In what is called a floating car technique, I attempted to travel according to the speed limit of 60 kph. I also tried my best to keep my lane, only changing when it was necessary. I also tried to count how many vehicles would pass me, indicating how many traveling my way were faster than me and therefore over-speeding.

The first thing I noticed when I entered Commonwealth from University Avenue was that buses and cars were again zipping by me and so I didn’t bother anymore to count those passing me. I did maintain my speed so I could have a reference as to how fast the other vehicles were relative to mine. Approaching the Fairview Market area, I also observed that people were crossing almost anywhere and that some barriers have been moved to allow jaywalkers to cross the median. Meanwhile, the pedestrian overpasses were all crowded and I could see the entire length also occupied by vendors. Not an enforcer was around to bring order in what was a chaotic marketplace scene – along a major highway.

I repeated the experiment in the afternoon when I drove from my in-laws home to my parents’ home. Taking the opposite direction, Commonwealth was even more congested when I approached the Fairview Market area. Buses, jeepneys and tricycles practically took up 3 lanes, stalls, hawkers and pedestrians took up 2 lanes and there was only 1 left for all other vehicles to pass through. No one among those who clogged the highway seemed to care and I again saw no enforcers to mahage traffic. If there were, I’m sure they were somewhere else and definitely not doing their jobs.

It is both disappointing and frustrating that the traffic discipline program along Commonwealth went the way of ningas cogon. In fact, the MMDA seemed to have celebrated what they thought was success prematurely, even stating that they were to apply similar strategies to other major roads in the Metro. By the looks of the outcomes along Commonwealth, such efforts along other roads will eventually go the way of ningas cogon. Such results send the wrong message to motorists and pedestrians and reinforce the perception that the authorities don’t really mean business and that such programs are just for show. So far, it seems that this perception will continue to pervade along Metro roads unless the MMDA, the PNP and the respective local government units get their acts together. Again, it shows that going back to the basics remain the main challenge and overcoming the ningas cogon tendency the main obstacle for our authorities.

Discipline along a killer highway

Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City was given a tag as a killer highway due to the frequent occurrence of road crashes along the road, many of them resulting in fatalities. Only last December, a retired judge was about to cross the highway on his vehicle, his wife (a retired teacher from a prestigious science high school) with him as they were heading to church. It was very early in the morning since they were going to the Simbang Gabi or night mass – a tradition in the Philippines during the Advent Season leading up to Christmas Day. Despite probably signalling and their being cautious enough, their vehicle was hit by a speeding bus. The driver of the bus was to claim later that he used his lights and horns to warn the judge against crossing. There was no mention if the bus driver attempted to slow down, the safest thing to do when driving at night and knowing that there are many crossings along the road he is traversing. In fact, this should be the first thing on the mind of anyone aware and conscious about safe driving.

There are many incidents like the one above and not just along Commonwealth or other Metro Manila road. Road crashes occur along many of our national and local roads everyday and the casualties just pile up, and many are often just treated as statistics especially when nothing is done to address the issue. Such road crashes occur due to many factors that are usually categorized into human, vehicle or environment-related. Most often, as findings in the Philippines indicate, it is the human factor that results in a road crash.

Driver error, poor maintenance of vehicles, and ill-designed roads can all be traced to human shortcomings. Environmental factors are also ultimately rooted on the human element. Speeding is one thing and aggressive driving is probably another but altogether general driver behavior along Philippine roads are clearly a manifestation of a lack of discipline and not necessarily the lack of skill, although the latter is also a significant factor if one is to focus on public transport and trucks.

There are few exceptions and it seems “few” is a relative term often leading to the example of Subic. At Subic, we always wonder how and why drivers seem to be disciplined. Some say it is because of the fines or penalties for traffic violations. Others say it is psychological and a legacy of the base being previously under the US military. I would say it is more of the traffic rules and regulations being enforced firmly and fairly in the free port area. I would add that motorists and pedestrians have embedded this in their consciousness such that there is something like an invisible switch turning on when they drive in Subic and turning off once they are out of the free port.

For a corridor like Commonwealth, perhaps the best example to emulate would be the North Luzon Expressway (NLEX). Along that highway, its operators the Tollways Management Corporation (TMC) have established a strict regimen of enforcement and have applied state of the art tools for both monitoring and apprehension. These tools include high speed cameras equipped with speed radars that detect speeds and capture on photo cases of overspeeding. Photos are used as evidence upon the apprehension of the guilty party at the exit of the expressway.

The current campaign along Commonwealth is premised on the strict enforcement of a 60 kph speed limit along the arterial and the designation of PUV lanes (e.g., yellow lanes) along the length of the corridor. The initiative would be manpower intensive and features novel tools such as the use of placards, loudspeakers and public relations in order to encourage motorists and pedestrians to follow traffic rules and regulations. The results as of today look promising and there has been a significant reduction in speeds and general compliance for PUVs serving the corridor. The numbers might be misleading if we attempt to conclude about the success of the program now. Perhaps the more reliable statistics would come out after the campaign has been implemented and the effort sustained over a month’s time. Nevertheless, it gives us a nice feeling to see less speeding and less weaving among vehicles that were once observed as though they were driven along a race track. It would be nice to once and for all kill the “killer highway” tag and make Commonwealth an example of how traffic management should be implemented. We are always searching for examples of good if not best practices that can be replicated elsewhere. If we succeed in the “Battle of Commonwealth” then perhaps we could eventually win the “War Against Irresponsible Driving and Jaywalking.”

Odd-Even Now? (Conclusion)

“The papers tackle various traffic schemes implemented in Metro Manila and focuses on the impacts and effectiveness of the UVVRP (Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program or number coding) in particular. Unfortunately, at the time the studies did not include evaluation of the Odd-Even scheme although such is mentioned in the first paper as the precursor of the UVVRP. Please note that these schemes are classified among vehicle restraint options that include the truck ban. Color-coding, number coding and the odd-even schemes were originally implemented as short term measures intended to be modified or lifted once the infrastructure projects that were then being implemented (overpasses and underpasses, coordinated and adaptive traffic signals, etc.) were completed. The UVVRP was indeed modified to include a window from 10:00AM – 3:00PM. Meanwhile, some LGUs in the periphery of Metro Manila no longer implement the UVVRP since they do not have much congestion unlike those LGUs where traffic converge along major thoroughfares such as EDSA, C5, C3, Gil Puyat, Espans and Quezon Ave. and Commonwealth. Incidentally, many of these roads are found in Quezon City.

The perceptions on the potential negative impacts of an Odd-Even scheme for EDSA are well founded since vehicles displaced will naturally be diverted to other roads. We have to be careful though not to call such roads simply as side streets or alternate routes since C5 (Katipunan (in QC)-E. Rodriquez (Pasig)-CP Garcia (Makati-Taguig), C3 (Araneta Ave.), Shaw Boulevard, Quezon Avenue and others are major arterials and form part of the circumferential and radial road system of Metro Manila. We are to expect more congestion along these roads that will, in effect, marginalize potential gains along EDSA.

The recommendation therefore, is for the MMDA not to experiment on EDSA from November 2010 to January 2011 but instead undertake in-depth analysis of the implementation of an Odd-Even scheme. Direct experimentation while effective in some cases will without doubt place much of the burden on the people using EDSA and other major roads. It is known that MMDA has acquired the capacity to simulate traffic based on their recent presentations. Perhaps this should be done for the entire stretch of EDSA and include all major roads affected considering that they will bear traffic diverted from EDSA. Such traffic simulation should, however, be properly calibrated and validated to reflect real world conditions. This is because it is also easy to come up with simulations whose results are partial or biased on what the simulator wants to show.”

Truck Ban

Another form of vehicle restraint focuses on freight and logistics vehicles, particularly trucks. These are commonly referred to as large vehicles having at least 6 tires (double-tired rear axle). The prevailing perception is that many if not most of these vehicles are overloaded and impede the flow of traffic due to their slow speeds as well as damage pavements not designed for heavy vehicles.

“The truck ban is a scheme first applied in the late 1970’s to address the perception that freight vehicles are the main culprits in congesting Metro Manila roads. Trucks were prohibited from traveling along major arterials including the primary circumferential and radial road network for most of the day. Exemptions from the daytime ban were applied to roads in the vicinity of the port area where truck traffic was practically inevitable.”

The coverage area of the truck ban included all of Metro Manila’s major circumferential and radial roads – C1 to C5 refer to Metro Manila’s circumferential roads while R1 to R10 refer to the radial roads. These comprise the main arterials of the Metro Manila road network. For reference, C3 refers to Araneta Avenue and related roads, C4 is EDSA, Letre and Samson Roads, and C5 refers to Katipunan, E. Rodriguez and C.P. Garcia Avenues. R1 refers to Roxas Boulevard, R5 is Shaw Boulevard, R6 is Aurora Boulevard, and R7 is España and Quezon Avenues.

“There are the different versions of the truck ban being implemented in Metro Manila. Truck Ban 1 is enforced along EDSA, Metro Manila’s busiest arterial and often its most congested road. Designated as Circumferential Road 4 (C4) it has a 10- to 12-lane carriageway with a mass rapid transit line running along its median. Truck Ban 2 practically covers all other roads except sections of arterial roads that have been designated as truck routes.”

Truck Ban 1 is enforced from 6:00 AM to 9:00 PM everyday except Sundays and Holidays. Meanwhile, Truck Ban 2 is implemented from 6:00 AM to 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM to 9:00 PM everyday except Sundays and Holidays. The second version attempts to minimize trucks during the morning and afternoon/evening peak periods.

“The chronology of the truck ban scheme started in 1978. In recognition of the critical situation of traffic congestion in Metro Manila, the then Metropolitan Manila Authority (MMA) issued Ordinance No. 78-04, which prohibited cargo trucks, with gross vehicular weight (GVW) of more than 4,000 kilogram, from plying along eleven major thoroughfares in Metro Manila during peak traffic hours – from 6:00 A.M. to 9:00 A.M. and from 4:00 P.M. to 8:00 P.M., daily except on Saturdays, Sundays and holidays.

In 1990, the Department of Transportation and Communication (DOTC) issued Memorandum Circulars No. 90-367 and 90-375, changing truck ban hours to: between 7:00 A.M. and 10:00 A.M. on weekdays; 4:00 P.M. to 8:00 P.M. for Monday to Thursday; and from 4:00 P.M. to 9:00 P.M. on Fridays. In response to the appeal of the members and officers of the various truckers’ associations for an alternate route and a 2-hour reduction of truck ban, the MMA issued Ordinance No. 19, Series of 1991, amending MMC Ordinance No. 78-04. This issuance provided alternate routes to the truck ban routes and effected a 2-hour reduction of the truck ban period, thereby prohibiting trucks on the road from 7:00 A.M. to 9:00 A.M. and from 5:00 P.M. to 8:00 P.M.

In 1994 the MMA issued Ordinance No. 5, Series of 1994, further amending Ordinance No. 78-04 as amended by Ordinance No. 19 Series 1991. The Ordinance restricts trucks from traveling or passing along 10 major routes from 6:00 A.M. to 9:00 A.M. and from 5:00 P.M. to 9:00 P.M. daily, except on Saturdays, Sundays and holidays. The Ordinance also provided for an “all-day” truck ban along Metro Manila’s major arterial road, the Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA), from 6:00 A.M. to 9:00 P.M. daily, except Saturdays, Sundays and holidays.

In 1996, the MMDA, in its desire to further reduce traffic congestion even on Saturdays, issued Regulation No. 96-008 amending MMA Ordinance No. 94-05, imposing truck ban from Monday to Saturday, except Sunday and holidays. An MMDA Regulation No. 99-002, amended Ordinance No. 5, Series of 1994, wherein the “gross capacity weight” was amended from 4,000 to 4,500 kilograms.”

In the last few years, the MMDA has implemented adjustments to the truck ban scheme in coordination with Metro Manila local government units. Certain truck routes were identified to address the issues raised by the private sector, particularly industries and commercial establishments, regarding the transport and delivery of goods. Other cities in the Philippines have adopted the truck ban in one form or another, often directing trucks to use alternate roads in order to decongest the roads in the central business districts as well as to prevent their early deterioration as a result of truck overloading practices.

[Source of italicized text: Regidor, J.R.F. and Tiglao, N.C.C. (2007) “Alternative Solutions to Traffic Problems: Metro Manila in Retrospect,” Proceedings of the 11th World Conference on Transport Research (WCTR 2007), 24-28 June 2007, University of California Transportation Center, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, DVD.]